Seventeen-year-old Eli Cooper gets a cooking lesson from his mother, Jennifer (photo by Elisabeth Fall).

Improving Partnerships to Make Family-Centered Care Work for Children with Special Health Care Needs

If, as the proverb goes, it takes a village to raise a child, it can take a small army to raise a child with a complex, chronic health problem. Families have to navigate a maze of systems and services – medical, educational, psychological and financial – that overlap but often don’t connect or are at odds with a family’s true needs. For many families, it’s a journey without a set destination and no road map.

The challenge is complicated by the fact that due to improvements in medical and surgical care, increasing numbers of children with chronic, complex health problems survive into adulthood, while technological advances have allowed children who in the past might have needed the support of a hospital or other high-resource institution, to remain at home.

This puts families more squarely at the center of caregiving, a place that can be at once gratifying and frustrating.

Who Are These Families?

According to the 2011/12 National Survey of Children’s Health, there are nearly 14.6 million children in the US with special health care needs, defined by the federal Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) as “those who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.”

Roberta Rehm The MCHB’s list of diagnoses covered by the definition includes conditions as diverse as diabetes and developmental disorders. “It’s important to know who you’re talking about when you look at these families, but there are crosscutting issues,” says Roberta Rehm, associate professor of family health care nursing at the UC San Francisco School of Nursing, who studies families of children with chronic, complex conditions. While the children have a broad spectrum of needs, says Rehm, common challenges facing such families include “access to health care and to support that helps them to optimize their children’s functioning, and stigma.”

Roberta Rehm The MCHB’s list of diagnoses covered by the definition includes conditions as diverse as diabetes and developmental disorders. “It’s important to know who you’re talking about when you look at these families, but there are crosscutting issues,” says Roberta Rehm, associate professor of family health care nursing at the UC San Francisco School of Nursing, who studies families of children with chronic, complex conditions. While the children have a broad spectrum of needs, says Rehm, common challenges facing such families include “access to health care and to support that helps them to optimize their children’s functioning, and stigma.”

Siloed Services and Broken Family-Provider Relationships

One of the key challenges is that help is out there, but it’s often uncoordinated and hard to access, says Juno Duenas, executive director of Support for Families of Children with Disabilities, a parent-led organization that provides resources for Bay Area families of children with special health care needs. “Let’s say I’m a parent who’s just found out my child has autism. I don’t know where to go or who to talk to. I have no clue where to start,” she says, citing a bewildering array of agencies operating at the federal, state and local level: California Children’s Services, mental health services, special education districts, regional centers for individuals with developmental disabilities, Social Security and Medicare/Medicaid. Each provides different services, and each has its own eligibility requirements and regulations. Says Duenas, “They’re all wonderful systems, they provide important services, but they don’t work together.”

The fragmentation also makes changes to a family’s circumstances a particularly difficult challenge. Available services, eligibility, and funding and delivery of services differ across states, and even across counties; families who move often find themselves starting over to set up services, or they may have to travel long distances to access appropriate ones. Moreover, a family’s needs will change over time. “As the child grows and changes, the systems change. So the families are often caught by surprise,” says Duenas.

Such “siloing” doesn’t just occur between services; it can also characterize the relationship between providers and family caregivers. The point of entry into the world of special needs for many families is the health care system, which is often ill equipped to help families navigate the maze of services. And the training and time demands of many providers can sometimes blind them to the realities that face families as they try to care for their children on a daily basis.

Jennifer Cooper, whose 17-year-old son, Eli, has Down syndrome, recalls struggling with physicians’ recommendations early on. Like many people with his condition, Eli has gastroesophageal reflux and, as a toddler, suffered from bouts of pneumonia caused by microaspiration – breathing in small amounts of swallowed and regurgitated material. When Eli was discharged from the hospital, the Coopers were advised not to give him thin fluids. “But nobody tells you how to make that happen,” says Cooper. “They just said, ‘Go get some Thick-It [a food and beverage thickener]; insurance might cover it, they might not. You can see a nutritionist if you want.’ You’re on your own.”

Oscar Hill (left) with his parents, Paul and Mary, and siblings, Abe and Ruby The doctors’ advice proved very difficult to follow. Because his throat was often irritated, Eli craved water, which he couldn’t have, and Cooper felt as if she were torturing her son. “He would crawl up to the dishwasher and lick it. During the rainy season, I couldn’t let him out of his stroller because he’d try to lick the puddles.” Cooper often feels as if she isn’t being heard by the medical professionals. “There aren’t a lot of questions being asked before they make recommendations,” she says. “Eli’s oral motor muscles are weak and uncoordinated. Doctors have recommended chewing on things like beef jerky and taffy. They don’t understand that Eli has intense food aversions and sensitivities – he literally only eats 14 items. Those suggestions would not only fail, but would just further frustrate us.”

Oscar Hill (left) with his parents, Paul and Mary, and siblings, Abe and Ruby The doctors’ advice proved very difficult to follow. Because his throat was often irritated, Eli craved water, which he couldn’t have, and Cooper felt as if she were torturing her son. “He would crawl up to the dishwasher and lick it. During the rainy season, I couldn’t let him out of his stroller because he’d try to lick the puddles.” Cooper often feels as if she isn’t being heard by the medical professionals. “There aren’t a lot of questions being asked before they make recommendations,” she says. “Eli’s oral motor muscles are weak and uncoordinated. Doctors have recommended chewing on things like beef jerky and taffy. They don’t understand that Eli has intense food aversions and sensitivities – he literally only eats 14 items. Those suggestions would not only fail, but would just further frustrate us.”

The feeling of sometimes being disregarded by professionals resonates throughout the community of families of children with special needs. Oscar Hill has Prader-Willi syndrome, a genetic condition that typically causes a variety of symptoms, notably low muscle tone, insatiable appetite, behavior challenges and learning disabilities. His mother, Mary Hill, was told her son would need surgery to correct undescended testicles as a toddler because later he would be so fat that it would make the procedure more difficult. She recounts the discussion: “I said, ‘We’re managing his diet and we make sure he doesn’t have access to food, so that’s not going to happen.’ And the doctor said, ‘Of course it is; he has Prader-Willi.’”

Hill promptly found another doctor more willing to listen to her concerns. When the original surgeon contacted her to enquire about why she had left the practice, she told him, “I didn’t feel like you were hearing or respecting me.” She credits him for being receptive to her feedback, but when Oscar (who, at 12, maintains a healthy weight) eventually underwent the surgery, it was with the second surgeon. “It’s not that I want to direct his medical care, but I appreciate being a partner,” Hill says.

A Push for Family-Centered Care

Partnership is at the heart of the movement toward what’s called “family-centered” care, which emphasizes respectful collaboration between families and professionals to deliver care that integrates emotional, social and cultural well-being into decisionmaking and planning.

The degree to which that happens can have a direct impact on quality of care. “Families are only going to do what they believe is best for their child,” says Nora Wells, co-director of the National Center for Family/Professional Partnerships, a project of Family Voices, a national family-led advocacy organization that promotes quality care for children with special health care needs. “If there’s a complete disconnect between what the system is saying you should be doing and what you’re doing, we’re not accomplishing much in terms of health care.”

The drive to incorporate a broader view of families’ needs into the definition of quality health care started largely with families themselves, via grassroots organizations like Family Voices and Support for Families. As families began to play a larger role in the care of their children with disabilities, attitudes and policies within the health care system didn’t keep pace, and families were left with lots of responsibility but too little support or authority. “We’ve been at the mercy of whatever systems grew up,” says Wells. The problems ranged from limitations on parents’ visiting rights in hospitals to laws that required institutionalization in order to receive Medicare/Medicaid coverage of certain services.

“We started out in the 1980s with the idea that if you could improve communications between providers and families, you could improve care,” says Wells. This effort has required a shift in the health care culture that, for more than a century, placed physicians at the top of a hierarchy, with patients and caregivers at the bottom, deemed “compliant” or “noncompliant.” Such a dichotomous view ignores the undeniable expertise parents and other family caregivers bring to the table regarding their children.

Professionals may be the experts in a particular condition or in providing acute care, but parents and caregivers are the experts in how the condition affects their child, says Rehm. “One of my goals as an educator for nurse practitioners is to help them see the larger picture of children in a family setting. I hope to help them see the family’s expertise and to feel that as health care providers, they have the obligation to negotiate with parents as equals for the benefit of the child,” she says.

Asking Families to Define Quality

While most stakeholders agree that family-centered care is crucial to quality, it has been difficult to define it in practice. One of the challenges, says Wells, is that families themselves haven’t had much voice in creating the definition. To change that, Family Voices has partnered with the MCHB to develop and validate the Family-Centered Care Assessment, a tool that uses 24 questions to measure the family-centeredness of provider care.

Rather than beginning with professionals to construct the assessment, they worked with a diverse group of families across the country to determine what quality family-centered care should look like. “We wanted to engage families themselves in the process at a deeper level,” says Wells, “so we began by asking families what they thought quality was and what was important in relationships with providers. That’s a very different place to start.” Thus far, the tool has been used by several children’s hospitals, medical homes and research projects, and Family Voices is working with the American Academy of Pediatrics to encourage pediatric practices to use it.

Finding Support Across Systems and Environments

While parents want to be treated as equals in the partnership, there is also a danger that they will become overburdened with responsibility while lacking the resources to follow through completely.

Linda Franck Linda Franck, chair of UCSF’s Department of Family Health Care Nursing, who has studied acutely and chronically ill children and the importance of the parental role in care, cautions against making assumptions about parents’ needs and desires. “Parents want to participate in decisionmaking, but sometimes they’re left to their own devices and feel like they’re not being supported,” says Franck. The parents or family caregivers often become de facto case managers, but, she continues, “It shouldn’t be out of desperation; it should be in partnership with someone on the health care team.”

Linda Franck Linda Franck, chair of UCSF’s Department of Family Health Care Nursing, who has studied acutely and chronically ill children and the importance of the parental role in care, cautions against making assumptions about parents’ needs and desires. “Parents want to participate in decisionmaking, but sometimes they’re left to their own devices and feel like they’re not being supported,” says Franck. The parents or family caregivers often become de facto case managers, but, she continues, “It shouldn’t be out of desperation; it should be in partnership with someone on the health care team.”

Coordinating care can become a full-time job, particularly when care encompasses everything from coordinating specialty medical care to ensuring the child has appropriate support in each environment. “The hardest thing for me is constantly having to manage all the aspects of Oscar’s care – medical, behavioral, educational and social,” says Hill. “Everything requires thought, research and extra time.” Oscar’s condition means his family must be vigilant about ensuring that his access to food is controlled, which means that Hill has to vet every environment – school, camp, other activities – carefully for food security. Oscar currently attends a school for children with learning disabilities in Marin County, a 30-minute bus ride from his home, where he can thrive without an aide. “He knows that I only put him in food-secure environments, which ensures that he’s safe and alleviates the anxiety that can arise when there’s access to or uncertainty about food,” Hill says.

Not all parents have the ability or resources to chase down the right environment and services. According to a 2013 report by the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health and the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, children with special needs and more complex conditions, children of families with low incomes or those using public insurance, and children of color in California experience significantly greater difficulty accessing appropriate health care and community services.

In San Francisco, Support for Families is actively looking for ways to reach families who may need extra help, and has recently partnered with the UCSF Medical Center and San Francisco General Hospital to place a staff member in primary care clinics to work with families with special needs. “There are those families who have a harder time finding services and need a lot more support. We’re going to try to find those families,” says Duenas.

Special Needs Require Specialized Knowledge

Because the impact of chronic conditions reaches into so many aspects of daily life, families of children with complex, chronic conditions must develop knowledge and skills beyond what’s required to raise a child with typical needs. Struggles with school districts for scarce special-education resources, lack of adequate housing or work opportunities after the transition to adulthood, and the cost of care not covered by insurance are common challenges. To be an effective advocate for a child with special needs can require knowledge of the arcane set of federal and state laws governing services for people with disabilities.

For example, says Rehm, who has conducted extensive research on issues surrounding the transition to adulthood for families of children with complex, chronic health needs, families of older teens face a dilemma when deciding how to approach the end of high school, and the choices they make can have implications down the line.

“Federal law entitles eligible children to receive special education services through age 21, but once you graduate and take your diploma – which many families want for their children – you lose that support,” she says. The other option is to receive an “alternative exit document” (with varying names and requirements in different states), which will allow the student access to postsecondary transitional services through age 21, but often prevents him or her from getting any postsecondary education and can limit job opportunities.

Looking for Models for Coordinating Care

There are models for coordinating care across systems, but they are generally localized or limited to specific conditions. Diabetes care is one example. At UCSF’s Madison Clinic for Pediatric Diabetes, nurses generate plans for managing a patient’s diabetes at school and regularly connect with school nurses to ensure patients’ needs are being met. They also encourage every family to work with the school to set up an Individual Accommodation Plan (known as a “504 plan” after the section of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973 that requires publicly funded schools to provide support for students with disabilities).

Maureen McGrath “It’s taken 20 years for this to become a universal recommendation,” says Maureen McGrath, associate professor in the Department of Family Health Care Nursing, “but now it’s routine.” At UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland’s Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center, a pediatric social worker is assigned to each child with sickle-cell disease to help families advocate for their children in the school system. “If a parent feels a child is struggling, we’ll go with them to the school to help get an IEP [individualized education plan] or 504 plan set up,” says clinical social worker Kimberly Major. At age 18, patients also receive services to aid in the transition from the pediatric to the adult health care system. “We follow a medical home model, and we really try to meet the families where they are,” says Major.

Maureen McGrath “It’s taken 20 years for this to become a universal recommendation,” says Maureen McGrath, associate professor in the Department of Family Health Care Nursing, “but now it’s routine.” At UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland’s Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center, a pediatric social worker is assigned to each child with sickle-cell disease to help families advocate for their children in the school system. “If a parent feels a child is struggling, we’ll go with them to the school to help get an IEP [individualized education plan] or 504 plan set up,” says clinical social worker Kimberly Major. At age 18, patients also receive services to aid in the transition from the pediatric to the adult health care system. “We follow a medical home model, and we really try to meet the families where they are,” says Major.

Coping with Stigma and Judgment

Even with support, the pressures can go beyond the practical and financial. Families of children with special needs can suffer from stigmatization and isolation. Moreover, families of children with special needs sometimes face a mountain of judgment. They regularly grapple with the perception that they did something wrong to have a child with a disability or illness, or expressions of resentment at the “burden” those with disabilities place on society, or criticism from those who are less than understanding of behavior problems, particularly if their children “look normal.”

Says Duenas, who has an adult daughter with a disability, about her own past experience: “Because I have a child with a disability, everybody feels like they have the right to look in my window and comment. And it’s hard, because you get judged for every little thing you do.”

It doesn’t just come from the outside. It can come from other parents of children with special needs – or from within the family – about therapies tried or not tried, and from providers, who may disapprove of a family’s “noncompliance” with recommendations.

“I felt so much judgment from his physical therapist and doctors,” says Cooper, who withdrew Eli from physical therapy at 18 months of age when she realized how traumatic it was for him.

The decision to quit came when she realized that whatever benefit he might get from the therapy was offset by harm to other aspects of his development. “We were trying to work on his communications skills,” she says, “and during therapy, he was using his words and pointing ‘down,’ and the therapist was ignoring him. I thought, ‘Okay, we’re just showing him that we don’t care about his words and they don’t have any power.’ It was so hard. We would both leave in tears.”

Facing the Future with Optimism and Commitment

Despite the challenges, in her research Rehm has found that most families of children with special health care needs tend to emphasize the “normal” aspects of life. “They try to focus on the things they can do and how they can optimize them,” says Rehm.

Despite the challenges, in her research Rehm has found that most families of children with special health care needs tend to emphasize the “normal” aspects of life. “They try to focus on the things they can do and how they can optimize them,” says Rehm.

In fact, while there is still a long way to go to realize the dream of supportive, accessible, coordinated, family-centered care for all children with special health care needs, most families remain optimistic about their children’s prospects. They are determined to help their children maximize their opportunities – and many are finding both expected and unexpected rewards, a pride in moments that those who don’t have the same experience may never fully understand.

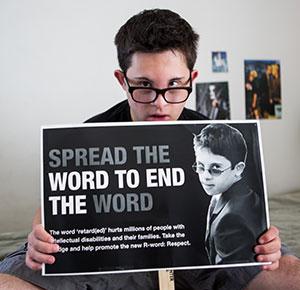

With support from his mother and a circle of typically developing friends, Eli Cooper regularly speaks in schools and community centers about his life and about the Spread the Word to End the Word campaign, which urges people to stop using “retarded” to refer to people with intellectual disabilities. “It’s been hugely empowering for him,” says his mother. “He loves to be in front of an audience, and he can see himself as an educator and leader. It’s been the one thing that has allowed him to see his disability in a positive light and accept it a bit more.”

Mary Hill recounts a physician saying shortly after Oscar’s birth that he would “never ride the little yellow school bus” so often associated with children with special needs. Hill believes it was a misguided attempt to reassure her that Oscar would not be associated with those children.

“But Oscar did ride the little yellow school bus,” she says. “And I was so proud when he got off that first time, holding his little backpack. I wanted to send the doctor a picture saying, ‘See? He did ride the bus after all. I love this little guy, and I’m so proud of how far he’s come…even learning to ride the little yellow school bus independently.’”