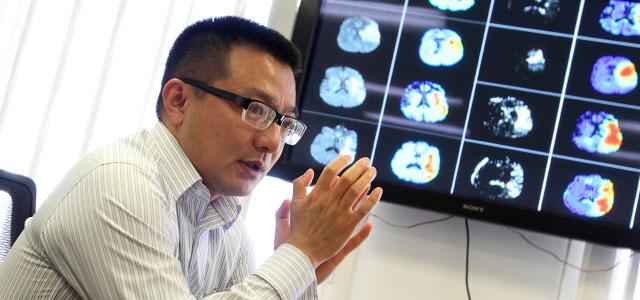

Xiao Hu, one of the first biomedical engineers in the country on faculty at a school of nursing.

Making Digital Sense of the Body’s Complex Signals

Drawn to UC San Francisco School of Nursing by the opportunity to work with a unique team of nurse scientists trying to solve the dangerous problem of alarm fatigue, on September 1 Xiao Hu became one of the first biomedical engineers in the country on faculty at a school of nursing.

His professional journey to this point is the story of a man driven to use his technological expertise to solve health care and biomedical challenges.

Seeking Opportunities in the US

After receiving his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China in Chengdu, Hu saw few opportunities in his homeland for a discipline about which he was passionate.

“I am a die-hard biomedical engineer,” he says. “Many of my classmates changed their focus, but I was able to come here to America, where people are doing great biomedical engineering research.”

While pursuing his doctorate at UCLA, which he completed in 2004, Hu chose to focus on modeling intracranial pressure and cerebral blood flow, significant factors in the diagnosis, treatment, monitoring and management of brain injury and stroke. His work was impressive enough to land him a faculty position at UCLA’s Department of Neurosurgery, which Hu says was a tremendous learning experience. He remains an adjunct faculty member there.

“Early on, I realized how important it was to team up with domain experts,” he says. “The neurosurgeons’ deep understanding of the pathophysiology of people with brain injury is what enabled me to leverage my training to refine problem formulations and then solve them using well-established engineering tools.”

The tools emerge from two areas in which Hu had become an expert and which are essential in medical monitoring: signal processing and machine learning. These engineering disciplines may mean little to most health care professionals, but Hu speaks eloquently to their importance.

On signal processing: “Historically, physicians focus on one number when assessing intracranial pressure,” he says. “But intracranial pressure is a complex signal, with lots of information hidden in the waveform it creates. If we don’t understand signal processing, we lose the chance to use all of the waveform information to make earlier, more accurate diagnoses of intracranial conditions.”

From Intracranial Pressure to Alarm Fatigue

This ability to get the most thorough and accurate information from the body’s “signals” plays directly into Hu’s second area of expertise: machine learning, an element of artificial intelligence in which computers are taught to generate or modify algorithms based on changing data inputs.

This ability to get the most thorough and accurate information from the body’s “signals” plays directly into Hu’s second area of expertise: machine learning, an element of artificial intelligence in which computers are taught to generate or modify algorithms based on changing data inputs.

The combination of the two disciplines is especially potent in Hu’s reason for coming to UCSF: working with a Barbara Drew-led team that seeks to address alarm fatigue, which is one of the nation’s most pressing patient safety problems. Alarm fatigue is caused by an array of highly sensitive patient monitors that trigger hundreds of alarms per hospital bed per day, causing clinicians to either tune out or turn off the monitors.

“Dr. Hu has established himself as an expert in analyzing continuously monitored physiologic signals from critically ill patients and in developing predictive models of patient deterioration that would alert doctors and nurses that their patient is heading for trouble,” says Drew. “We have plans to collaborate to improve patient outcomes and reduce clinical alarm fatigue by developing new algorithms to create smarter alarms that are clinically meaningful and reduce alarm burden.”

Today, most monitors (whether they’re for blood pressure, oxygen saturation, heart rhythms or another clinical concern) analyze only the clinical information in their silos. Drew, Hu and their colleagues hope to find ways to integrate information from multiple monitors, electronic medical records and, in the future, molecular data – and then to create sophisticated algorithms that are better at striking the balance between sensitivity (not missing any important clinical information) and specificity (only triggering alarms when a combination of factors indicates a need for action).

Machine learning is crucial here, because such monitors would need to intelligently generate their own unique algorithms based on the changing and growing data stores that the system and each individual patient generate.

Hu understands that this can sound frightening as it seems to place clinical analysis in the hands of machines, but he says the algorithms are always rooted in clinical expertise and evidence-based parameters. Moreover, any advances will have to pass rigorous evaluations, both from peer scientific reviewers and from federal regulators.

NASA, Mars and Beyond

Hu’s work is not just of interest to hospitals and physicians; NASA is also interested, in part because Hu’s expertise can help the agency in its efforts to send humans to Mars.

One of the concerns around these efforts is that astronauts develop vision problems after a long time in space. Some theorize that the problems are related to the impact of excessive intracranial pressure on the optic nerve. At this point, however, intracranial pressure can only be assessed invasively. Recently, Hu won an InnoCentive Challenge from NASA, by describing a potentially portable and noninvasive way to take the same measurement.

“It’s another opportunity to make a difference,” he says.

Hu appears to relish such opportunities, which explains his love of both biomedical engineering and his attraction to UCSF. It was a big decision to move from Los Angeles, as it meant selling his house and uprooting his wife and 2-year-old daughter, but Hu is excited by the possibilities.

“I really wanted to partner with Barbara to solve the alarm fatigue issue – and work with people like Chris Miaskowski, Brad Aouizerat and Glenna Dowling, who have been very supportive,” he says.

“We are extremely fortunate to have Dr. Hu join our faculty,” says Dean David Vlahov. “He will catapult our nurse-technology interface and informatics research agenda. He also is a delight to work with, and this partnership will create and strengthen ties across the campus and with industry.”

Hu clearly hopes so. He says, “At UCSF, it seems the barriers to meaningful collaboration across campus are pretty low, and I’m looking forward to more than 20 years of productive work here.”