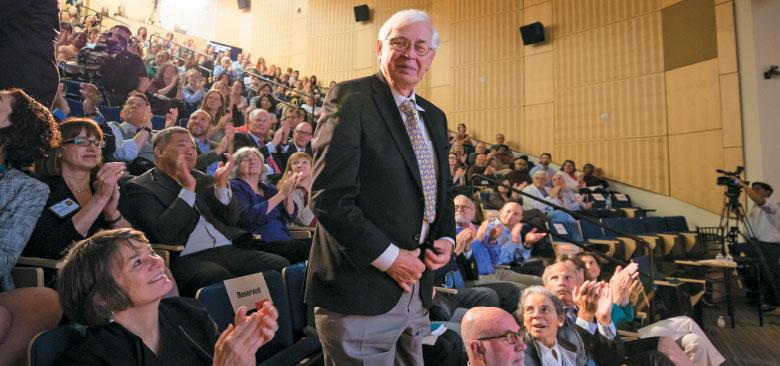

Dean Catherine Gilliss and David Mortara at the UCSF State of the University address on October 28 (photo by Elisabeth Fall)

Landmark Gift Establishes Center to Improve Monitoring, Address Alarm Fatigue

Last year, when David Mortara, a renowned leader in electrocardiogram (ECG) technology and innovation, retired and sold the company he had built, he started to think about what he still wanted to accomplish.

“What problem could I solve and in what framework could I do it?” he says. He determined that reducing alarm fatigue – where too many unnecessary alarms desensitize clinicians to true, actionable concerns – is an important and achievable goal. Alarm fatigue is widely recognized as a significant patient safety concern, which in some cases has demonstrably cost lives.

To address alarm fatigue and improve the use of physiological monitoring technology, Mortara has donated $25 million to the UC San Francisco School of Nursing – the largest gift in the School’s history – to establish the UCSF Center for Physiologic Research (CPR). Mortara chose the School because nurses are health care’s monitoring experts and because he has enjoyed a long and fruitful research relationship with School researchers, especially Professor Emerita Barbara Drew.

Engineer and Entrepreneur Meets Nurse-Scientist

From left: Barbara Drew, David Mortara, Tina Mammone (photo by Elisabeth Fall) After receiving his doctoral degree from the University of Illinois in 1973, Mortara applied his pattern recognition expertise to automating ECG analysis for a small company in Chicago. A move to Marquette Electronics (now part of GE Medical Systems) allowed him to add hardware development to his portfolio. He was among the first in the ECG field to marry hardware and software design, helping develop the simultaneous 12-lead ECG acquisition and interpretation that is the basis for modern electrocardiography.

From left: Barbara Drew, David Mortara, Tina Mammone (photo by Elisabeth Fall) After receiving his doctoral degree from the University of Illinois in 1973, Mortara applied his pattern recognition expertise to automating ECG analysis for a small company in Chicago. A move to Marquette Electronics (now part of GE Medical Systems) allowed him to add hardware development to his portfolio. He was among the first in the ECG field to marry hardware and software design, helping develop the simultaneous 12-lead ECG acquisition and interpretation that is the basis for modern electrocardiography.

In 1982, he left Marquette to form his own company, Mortara Instrument (acquired by Hill-Rom Holdings, Inc., in 2017), where he continued to develop and refine ECG products and technology. Since its founding, the company has deeply valued its research arm, and within a few years, Mortara began seeking a research partner who could provide information and feedback on the clinical relevance of the company’s products and technology.

Around the same time, Drew was hired as tenure-track faculty at UCSF School of Nursing and was eager to establish her program of research. In her first National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded clinical trial, using a heart monitor made by Mortara Instrument, she demonstrated that looking at a particular part of the ECG – called the ST segment – could help predict which patients were at higher risk for poor outcomes.

At a conference of the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology, Drew recognized Mortara’s name on the program as one of the group’s founders, and introduced herself. “It turned out that he had been wondering who this nurse was in San Francisco who had ordered a batch of his monitors,” she says.

The meeting was the beginning of a two-decade-long collaboration dedicated to improving physiological monitoring of patients in and out of the hospital. “I realized that he was really an academic too,” Drew says of Mortara. “I knew I could learn so much from him because he knows what’s inside the ECG machine I’m using for my research. And he needed me because he didn’t know what things worked best for patient care and what nurses need.”

A Fruitful Collaboration

In 1991, Drew founded the School’s ECG Monitoring Research Lab, which has built an international reputation for research that has improved cardiac monitoring and clinical practice and influenced the development of monitoring technology. Over the years, Mortara and Drew, together with colleagues from the lab, have produced a number of influential, peer-reviewed papers on electrocardiology and patient monitoring.

These include a landmark study of five adult ICUs, in which Drew and her colleagues found that 461 patients generated more than 2.5 million unique alarms over just 31 days. Eighty-eight percent of the arrhythmia alarms logged were considered false positives, a disturbing finding given all that’s at stake.

In recognition of the value of this collaboration, in 2013 Mortara made his first significant contribution to the School when he endowed the Distinguished Professorship in Physiological Nursing Research to support the work being done by Drew and a coterie of her mentees, including faculty members Michele Pelter, Xiao Hu, Richard Fidler and Tina Mammone (now vice president and chief nursing officer at UCSF Medical Center). All are committed to improving monitoring and patient care – including development of a so-called “super alarm.”

Creating a Research Hub

Mortara hopes the CPR will become a hub where this type of interdisciplinary group of scientists can come together to solve pressing clinical problems without having to scramble for grant money that has become increasingly scarce.

“There are very few intersections like this around the world. If we don’t have a framework where [engineers and clinicians] interact, [ECG] becomes this bewildering technology that nobody feels like they can understand,” says Mortara.

Fortunately, the School has already begun to build that framework with the 2013 hiring of Hu –the faculty’s first engineer – and its deepening ties with UCSF Medical Center. That relationship is only set to expand with the recent hiring of Mammone as the medical center’s vice president and chief nursing officer. As a doctoral degree student, Mammone worked with Drew on ECG monitoring research, and she’s acutely aware of the issue on a practical level, given that she is responsible for overseeing nursing operations at all of the medical center’s campuses, including Mission Bay, Parnassus and Mount Zion.

“The center is a perfect avenue for the School and med center nurses to partner and really lead the nation [in addressing alarm fatigue]. We have a responsibility as an academic medical center to develop the science and practice, and having a dedicated center is innovative and welcome,” she says.

“And because of the endowment, the center isn’t dependent on public grants or grants from companies, which is a luxury few [research organizations] have,” Mortara says.

That’s key for the kind of research he wants to do, he says, because the problems of electrocardiology, monitoring and alarm fatigue aren’t “exotic” enough to attract big grants from government or corporations. In addition, past failures may have poisoned the well.

“There was a big effort about 20 years ago that spent a lot of money but didn’t accomplish anything, for complicated reasons. It’s lowered the probability of public funding, so I’m stepping in to provide the endowment,” he says.

Step One: A New Performance Database for Monitors

The center’s first project will be to create an annotated database from data the ECG Monitoring Research Lab has been collecting since 2013.

The center’s first project will be to create an annotated database from data the ECG Monitoring Research Lab has been collecting since 2013.

Pelter, who has directed the lab since Drew’s retirement in 2015, and who along with Hu and Fidler has maintained the data-collection project, says, “We have an enormous amount of data, and it needs to be put into a form that we can use.”

The sheer number of data points makes analyzing and annotating it a job too vast for a group of human researchers to do, but a carefully designed combination of software and hardware could accomplish it, says Mortara. Careful analysis is essential because the data contains what Pelter calls “the truth about true and false arrhythmias” – those that have predictive value for patient outcomes and those that are just noise.

To illustrate the difference this could make, the most important database presently in use involves 24 hours of data from 48 subjects. That’s problematic, says Pelter, because patients don’t have lethal arrhythmias very often, and there is little predictive value in such small data sets.

“[Our database] will have very large numbers of these arrhythmias, so we’ll be able to see nuances and track outcomes,” she says. “For example, we’ll be able to say, ‘This particular rhythm only matters when it gets this fast.’”

In addition, Mortara hopes that if the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) eventually adopts the CPR database, it will give buyers the tools to determine which monitors provide better – and not just more – information. He also envisions the development of a “UCSF protocol,” which would draw on the database to develop best evidence for what we should be alarming for and how alarms should be set, depending on specific patient circumstances.

“It’s even possible that you could make these devices have different levels of alarms based on how educated and experienced the nurse is,” says Drew.

Such possibilities, however, depend on a marriage of technological and clinical expertise that rarely happens, according to Mortara; hence, his generous donation to create and sustain the CPR. Mortara expects to be directly involved in the center’s research and believes the School is an ideal place for passionate researchers and clinicians to come together to solve problems related to the physiological monitoring of patients.

“Nursing – especially here at UCSF – is a framework in which to actually do this work,” he says. “I’m working with people who really value it.”