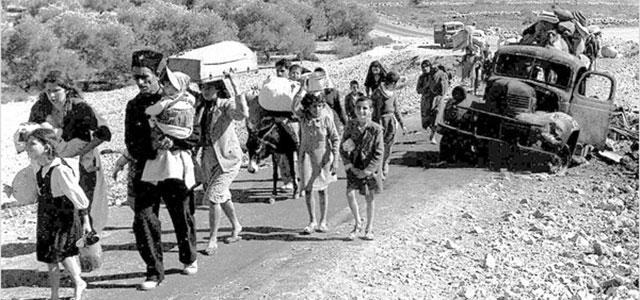

1948 Palestinian exodus into Jordan

Hamza Alduraidi: Forging a Path for Better Lives for Refugees

In 2007, when Hamza Alduraidi came face to face with a part of his family’s past, he decided what he wanted to do with his future. At the time, he was in his final year of nursing school at the University of Jordan, doing a clinical rotation in community and primary health care in the refugee camps that dot the areas surrounding the country’s capital, Amman.

“I realized that I belonged there; this was my passion,” says Alduraidi, a second-year PhD student in UC San Francisco School of Nursing’s Department of Community Health Systems.

A Personal Connection

Alduraidi considers himself a “fourth-generation half refugee.” His grandparents were among the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians displaced by the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Many of them flowed over the border into Jordan, including Alduraidi’s grandmother and grandfather. Only children at the time, they met in the Wihdat camp (known internationally as Amman New Camp), ultimately married there and made a life there along with their children. One of those children is Alduraidi’s mother.

As Palestinian refugees in Jordan, they considered themselves lucky compared with refugees in areas where the political situation was more tenuous. “In Jordan, they had the right to become citizens and enjoy those rights and responsibilities,” says Alduraidi.

Hamza Alduraidi But lucky is a relative term; the family remained in the camp for more than two decades. Alduraidi’s grandfather worked rather than attending the camp school, and discovered a talent for photography, eventually becoming a professional photographer. Thanks to his hard work and prowess with a camera, the family was finally able to leave the camp in the 1970s and buy a house in Amman.

Hamza Alduraidi But lucky is a relative term; the family remained in the camp for more than two decades. Alduraidi’s grandfather worked rather than attending the camp school, and discovered a talent for photography, eventually becoming a professional photographer. Thanks to his hard work and prowess with a camera, the family was finally able to leave the camp in the 1970s and buy a house in Amman.

Nevertheless, Alduraidi grew up hearing stories about life in the camp. “They stood in line for food, for medication, for every single thing – they had to wait hours to get them,” he says.

His mother, who was 17 when she left the camp, told of tent classrooms and the canned fish and fish-oil pills UN workers used to distribute to ward off the malnutrition that afflicted the camp’s children. While some things have improved, says Alduraidi, the problems inherent in overcrowding – including communicable disease, domestic abuse and mental health issues – remain.

Taking Awareness Beyond Jordan

After finishing his baccalaureate nursing degree, Alduraidi began work as an RN at Amman’s King Hussein Cancer Center and started a master’s program in public health at the University of Jordan Faculty of Medicine. One aim – rooted in his early clinical rotation and his family’s history – was to eventually conduct research into the best ways to improve the health of refugees. Upon finishing his master’s in 2010, he became a researcher and teaching assistant in the university’s Faculty of Nursing, eventually supervising fourth-year students in their rotations in the camps. More and more, he began to realize how important it was to bring greater awareness of the plight of refugees to the rest of the world.

In terms of improving health care, he says, that means more and better research and teaching. “I want to publish high-quality research in important international journals so that scholars and stakeholders all over the world read about it and become more aware,” he says.

When Alduraidi told his grandfather about his plans for graduate research into the health of Palestinian refugees, his grandfather was touched and proud. “He had tears in his eyes, because he lived it, and he knows how ignorant the rest of the world is regarding this issue,” says Alduraidi.

After winning a competitive scholarship offered by the University of Jordan for study in the US, he was accepted to UCSF School of Nursing’s master’s program. “My first choice was to go immediately for a PhD, but although I had a master’s from the University of Jordan medical school, it didn’t fit the criteria, so I had to get a master’s in nursing.”

New Culture, New Experiences

It was difficult to leave his family, but in 2011, Alduraidi got on a plane for the first time and flew to the US. Although he spoke English, he still had some adjustments to make. “The first few weeks, I was totally lost,” he recalls. “I didn’t know what to say in certain situations. The whole culture – what people respect, what they avoid talking about – was different.” He credits his classmates with helping him “really learn how to live here, word by word and step by step.”

Building on Research for the Future

Alduraidi completed his master’s as well as the Global Health minor in 2013 and began his PhD program with his advisor, Catherine Waters. His initial work, including a literature review, confirmed for him how little attention has been paid to the health of refugees in the Middle East. Most of the published research, he says, has been observational.

“Most researchers haven’t done interventions to investigate the efficacy of different interventions inside versus outside the camp. They just tend to describe what’s going on,” he says. The literature review and two other papers on the health of Palestinian refugees are the building blocks for an ambitious dissertation project: Alduraidi aims to be one of the first researchers to go into the field and measure the differences in health-related quality of life inside versus outside the camps – and its effects on the physical and mental health of refugees.

If all goes well, Alduraidi will return to Jordan to begin data collection sometime next year. Once his PhD is completed, as part of the terms of his scholarship, he will return to teach in the University of Jordan nursing school and continue studying refugee health.

In the meantime, in addition to his studies, he’s working to raise awareness of the refugee issue among his fellow students and the faculty. It’s a task that Alduraidi understands must be undertaken with care and sensitivity, because it’s all too easy for any discussion touching on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict to become politicized.

Alduraidi is careful to avoid the politicization but believes that turning the attention of researchers and health care workers to the problem is the best hope for improving the health and lives of refugees.

“It isn’t about my political or ideological position; my focus is the humanitarian side,” he says. “I started as one individual, but I hope that we will eventually be an army of passionate people who want to change things.”