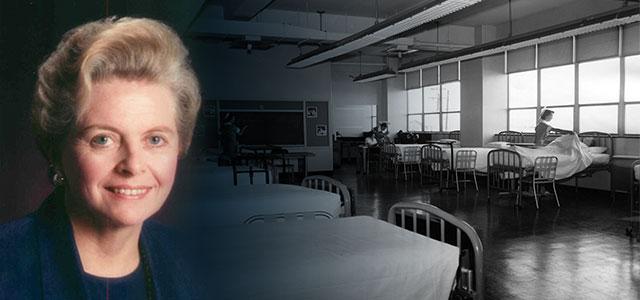

Shirley Chater

Gracious Force for Radical Change

To celebrate the 150th birthday of UC San Francisco and the role that the School of Nursing has played in this unique health sciences institution, Science of Caring is running a series of stories that focus on important, often seminal contributions that the School has made to health care delivery, education and research. Alumna Shirley Chater is among the School’s most prominent and accomplished graduates.

For more than half a century, Shirley Chater’s career in nursing, education and leadership has yielded a steady stream of high-level accomplishment and recognition. Yet it’s her contributions to fostering change in nursing, women’s rights and civil rights that make Chater’s career groundbreaking, even radical – if radical contributions can be so graciously rendered.

From her time as a student, professor and administrator at UC San Francisco School of Nursing and as the first female vice chancellor at UCSF (she has a UCSF Medal, the university’s highest award, and served as a UC Regents’ Professor) through her years running the Social Security Administration under President Bill Clinton, co-founding the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Executive Nurse Fellows Program and earning recognition in 2000 as a Living Legend from the American Academy of Nursing, Chater has civilly and compassionately forged a leadership path that continues to open doors.

Small-Town Values Shape a Career

Chater grew up in a small, working-class, Amish-influenced town in Pennsylvania. After working in the local physician’s office during one high school summer, she applied to nursing school, earning a full scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. After graduating with honors, she went on to earn a bachelor of science in nursing degree, even as she began teaching at the school.

Ultimately, though, inspired by her mentor at the University of Pennsylvania, Dean Theresa Lynch, Chater decided to pursue a PhD. Lynch encouraged her to look into UCSF, where, in the late 1950s, the School’s new dean, Helen Nahm, was creating innovative advanced degree programs for nurses.

But the School declined Chater’s application at first due to course-sequence irregularities, so she drove across the country, uncovered a little-known rule about being allowed to test into the program and proceeded to do so successfully. After completing her master’s in 1960 from UCSF, she completed her doctorate in education from UC Berkeley in 1964. At the time, the two schools’ programs were more closely linked than they are today.

“UCSF was quite small at the time; there were very few faculty, so the student-teacher relationships were very warm, practically one-on-one,” she says. “So many of the things I’ve accomplished spring from my time there and the people who taught and supported me.” Warm, respectful relationships would characterize much of the rest of Chater’s career and play an instrumental role in its advancement.

After getting her PhD, Chater immediately attained a joint appointment at UCSF and UC Berkeley, including taking over a research methods course in which she had served as a teaching assistant at UCSF. In the class, says Chater, “I was emphasizing the advantage of doing hard research that led to clinical applications.” She made sure to include guest lectures from sociologist Anselm Strauss, who was leading the newly formed Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, which Dean Helen Nahm had established and which Chater would eventually join as a faculty member.

Understanding the Challenges of a Working Woman Firsthand

As she began her career in academia, Chater also found herself juggling child care with her teaching and research schedule at a time when awareness and support for managing those challenges was on few people’s radar.

“There was no child care available at the university at the time – and none in the community,” she says. “I remember one time my son set fire to the back of our house. When a neighbor called me to tell me, she made a point of saying that if I’d been home full-time like a mother should be, it would never have happened. It was such a blow.”

Two relationships helped her through what could be a delicate balancing act. Most importantly, during her student years, she had married neurosurgery resident Norman Chater, who would remain supportive of her career right through his sudden death in 1993. She also formed a warm and lasting relationship with the woman who would help to provide child care for the Chaters’ children for 13 years.

Moving into Administration

Child care wasn’t the only difficult decision facing a young, ambitious nurse in changing times.

“I still remember talking with Helen Nahm (who had become a close mentor) about whether I could continue to focus on clinical work – I was in cardiovascular nursing – while also advancing through academia. Helen said that sooner or later I would have to decide [between the two paths].”

Eventually, Nahm offered and Chater accepted an administrative position, where she stayed until the school reorganized; that’s when Chater moved to the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, where she taught until, in the early 1970s, there was an opening for an associate vice chancellor for academic affairs.

Leslie Bennett “My women colleagues at the School of Nursing pushed me, promoted me, supported me for the spot,” says Chater. Moreover, the associate vice chancellor position was created by Leslie Bennett, the vice chancellor for academic affairs, who – while a professor of physiology at Berkeley – had been one of the people testing Chater for entry into UCSF. “I remember you,” he told her, when he interviewed her.

Leslie Bennett “My women colleagues at the School of Nursing pushed me, promoted me, supported me for the spot,” says Chater. Moreover, the associate vice chancellor position was created by Leslie Bennett, the vice chancellor for academic affairs, who – while a professor of physiology at Berkeley – had been one of the people testing Chater for entry into UCSF. “I remember you,” he told her, when he interviewed her.

As she assumed the position, she drew on what she knew.

“I often tell students that much of my approach to leadership comes from nursing,” she says. “It’s such a wonderful profession because it teaches observation, assessment, evaluation, leadership, communication – characteristics that translate and slide into whatever else you’re doing.”

Advancing Diversity

Chater says Bennett had created the associate vice chancellor position because of the emerging emphasis on affirmative action; her getting the job fueled an already active interest in the subject of campus diversity.

Soon, she was charged with writing a plan for expanding diversity on the UCSF campus at a time when few were paying any attention to the issue.

“All the vice chancellors from all UC campuses began to meet monthly on this and other issues, and Dr. Bennett would send me to represent him,” says Chater. “Now I was meeting with the big boys.… We all got along very well – I learned a lot from them and they from me – and I loved representing the campus in Dr. Bennett’s absence.”

The group eventually hammered out an affirmative action plan that the Academic Senate for all campuses approved.

Vice Chancellor: A First for Women, for Nursing

When Bennett moved on in 1977, Chater was his logical successor, but she doubted it would happen; the vice chancellor had always been a physician or someone related to medicine, not nursing.

“Again, it was the women on campus and my vice chancellor colleagues who nominated me. Honestly, though, there weren’t a whole lot of people who wanted that job since the major role was reviewing faculty for promotions and raises,” Chater says with a laugh.

When she got the job, she immediately became the highest-ranking woman in the UC system. In addition to fully implementing the affirmative action plan she and her colleagues had devised, she streamlined some of the review and evaluation processes and began the transition from paper to electronic record keeping.

But, she says, her most important role was transforming a very medical-centered campus into more of a health sciences campus.

“UCSF is much more than a medical center,” she says. “And new ways of looking at health were emerging from other places, especially nursing.”

To help speed this transition, Chater eliminated the separate meetings each of the deans held with the chancellor. “I thought if we worked together as a team and learned about how the whole operation works, we could stop competing so much over precious resources.”

Her concept had the full support of the chancellor at the time, Frank Sooy, whom she called “a wonderful, kind gentleman” – and another important mentor, whose modus operandi was to constantly seek common ground. “I learned the art of listening from him,” says Chater. “He taught me you had to listen to find common ground – and that without common ground, you can’t negotiate.”

A Career in Ascendance

Chater was not necessarily looking to leave UCSF when she went on sabbatical in 1984. The original plan was to work for a year in Washington, DC, for the American Council on Education, but she stayed two and caught the eye of people seeking a new president for Texas Woman’s University, a school with about half of its programs in health sciences and a large nursing program. It was a perfect fit.

Chater took the job, and in her seven years there, she navigated challenges that included fighting off a merger from day one, significantly restructuring the school to ensure its long-term survival and, once more, championing the causes of expanding diversity and supporting minorities on campus.

She achieved those goals through her trademark qualities of clear, honest communication and the search for common ground. She personally introduced herself to every group on campus – not just academic groups, but everyone who held a job on the campus – and, in the process, built relationships with powerful stakeholders across the state.

Then, in 1993, President Bill Clinton was looking for a commissioner for the Social Security Administration (SSA), at the time a subagency in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Chater’s name emerged, she believes, from three different sources: the American Nurses Association, which was lobbying hard to have a nurse in a high-level position in the administration; Governor Ann Richards of Texas; and former UCSF Chancellor Philip Lee, who had come to Washington to serve in HHS.

Once on the job, Chater again tackled significant challenges with remarkable skill. In addition to overseeing the SSA’s transition to an independent agency and facing an increasingly volatile Congress, she had to respond to the deadliest terrorist attack our country had ever experienced. In 1995 the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City was bombed, killing 149 adults and 19 children; 16 of the adults were SSA employees. Chater rejected advice that she stay away from the scene, arriving in Oklahoma City two days after the tragedy to offer comfort, speak with employees and oversee the agency’s role in recovery.

And she did all this in the wake of her husband’s sudden death shortly after their arrival in Washington in 1993. By the end of Clinton’s first term, she was ready to move back to the West Coast, to spend more time with her children and two newly born grandchildren.

Back to UCSF and Beyond

Moving on did not mean retirement. Her first stop was back at UCSF, which not only awarded her a UCSF Medal, but also named her a Regents’ Professor – a rare honor for a nurse in that position’s distinguished history. Chater spent much of the next year teaching and lecturing throughout the UC system.

Over the next decade and a half, she served as co-chair of the advisory committee for the UCSF/John A. Hartford Center of Gerontological Nursing Excellence and then became chair of the National Advisory Committee for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Executive Nurse Fellows Program, which gives top nurse executives advanced leadership training to help shape the constantly evolving health care system. She retired from the latter position in 2012.

“As Ann Richards taught me, you have to know when to hold ’em and know when to fold ’em,” says Chater.

Perhaps, but Chater has hardly folded her hand. She remains active as an independent lecturer and consultant working with organizations and individuals on management and leadership development – and still mentors many former and existing fellows. Now and then, she even comes back to speak at UCSF, despite spending most of her time either in Oregon, where she now lives, or with her children and grandchildren.

She hasn’t lost any of her enthusiasm, however, for mentoring the next generation of nurse leaders.

“Every single time I go someplace – college, professional meeting – I always meet a student or two,” she says. “And I love it. I love being in touch with this wonderful network.”