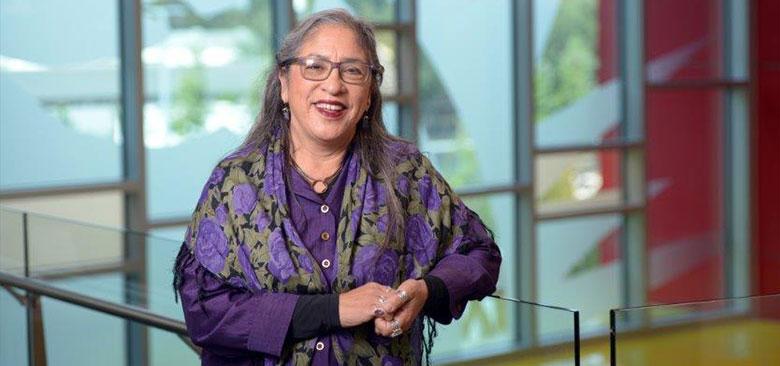

Luisa Buada (photo by Scott Buschman)

Caring for California’s Most Vulnerable Communities

Luisa Buada's career trajectory, on which she has had to overcome many challenges, has been untraditional for a nurse, but its driving force has always been the principles of social justice, equality and opportunity for all.“I grew up in San Francisco at the time of the Great Society, the War on Poverty and the creation of the Office of Economic Development. That’s been my guiding star,” says Buada (BSN ’77), CEO of the Ravenswood Family Health Center, a Federally Qualified Health Center that provides preventive and primary health care to the underserved community in and around East Palo Alto.

A Hidden Marriage

Buada’s exposure to the social justice issues that would resonate throughout her career began early. She was one of five children of a Filipino immigrant and a European American woman who were married at a time when state law still prohibited interracial marriage. The family lived in the Bayview District of San Francisco because it was one of the few places in the city where people of color could buy a home. Buada’s father, John, worked at the Hunters Point Shipyard, while her mother, Laurine, had graduated at the top of her UC San Francisco nursing class in 1942 and worked at Moffitt Hospital (now UCSF Medical Center).

“They got married out of state, and until she got pregnant with my older sister, my mother kept a separate apartment with another nurse to keep [the marriage] a secret, so she wouldn’t lose her job,” Buada says.

Working for California’s Farmworkers

Buada in Salinas, 1974 Buada excelled in the Catholic schools she attended as a girl. Some of her teachers introduced her to the plight of California’s impoverished farmworkers, and at age 15 she became involved with the United Farm Workers (UFW)’s efforts to improve conditions for lettuce and grape pickers in the Central Valley.

Buada in Salinas, 1974 Buada excelled in the Catholic schools she attended as a girl. Some of her teachers introduced her to the plight of California’s impoverished farmworkers, and at age 15 she became involved with the United Farm Workers (UFW)’s efforts to improve conditions for lettuce and grape pickers in the Central Valley.

When she arrived at UC Santa Cruz in 1971, Buada thought she wanted to become a teacher, but, ultimately, decided against it. She did, however, keep her focus on social justice, leading campus efforts to raise money for food and clothing for grape workers during the Coachella Valley grape strike of 1973, which ultimately won workers a contract with growers and the right to bargain collectively.

Spending time among the workers was a life-changing experience. Buada took a leave of absence from college and stayed in the Coachella Valley area following the strike, working as a Spanish-language translator for people applying for food stamps. Her desire to improve conditions for people in marginalized communities prompted her to consider a career in law, but she was quickly disillusioned by what she saw. “I went to see court cases, and it was all about technicalities; it wasn’t about justice. I was so upset,” she says.

On the Path to Nursing in the Salinas Valley

Buada’s transition to a career in health care began when a nurse invited her to become a volunteer translator for the UFW-run farmworker clinic in Salinas. The clinic was a two-bedroom house. The staff were all volunteers and lived together in one house, getting $15 a week and food stamps. The physicians – residents from Stanford University School of Medicine – spoke no Spanish, so translators like Buada were involved in every aspect of care, from taking histories to dispensing medication. Tight funding meant that everyone wore several hats, and Buada learned to do blood counts from Gram stains and incubate cultures in the lab.

“At once I was a nutritionist, a pharmacist and a lab person. It got me interested in pursuing a career in health care,” she says.

What Buada saw impressed upon her how deeply health disparities affected communities. In those days before the advent of the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), hospitals could turn away patients who couldn’t pay, even in emergencies. Buada was particularly affected by an expectant mother who had gone to the hospital with contractions and a feeling something was wrong. She was turned away, with tragic results. “The [umbilical] cord was wrapped around the baby’s neck, and it died in utero,” Buada says. “The mother later had a mental breakdown.”

For many in the Salinas Valley, the community clinic was the only place they could turn to for care. In addition to tending to their health needs, clinic staff became advocates for their patients who needed more care than they could provide. Buada recalls, “We used to go with women in labor and sit in the car with them in the hospital parking lot until the baby was almost crowning, then escort them in and advocate for them to be seen.”

At UCSF, Against the Odds

The medical residents she worked with suggested Buada go to medical school, but nursing seemed a better fit. She returned to school, splitting her time between Hartnell College in Salinas and UC Santa Cruz to complete her nursing prerequisites. When she went to the nursing director at Hartnell College to ask for advice on applying to the UCSF School of Nursing, she was initially rebuffed. “They told me there was no use applying there because people like me didn’t get into UCSF,” she says. By “people like her,” Buada, says, they meant anyone who wasn’t white.

Nevertheless, with outstanding marks in her prerequisites, Buada was accepted for the UCSF graduating class of 1977, one of the last before it ended its BSN degree program. During her time at UCSF, she remained active in social justice movements, including protesting Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, a case then heading to the U.S. Supreme Court that took aim at the affirmative action policy at the UC Davis School of Medicine. The case struck a nerve with Buada, who says that affirmative action allowed many of her friends to be the first in their families to attend college. (The court ultimately struck down that medical school’s policy of setting specific quotas for minority students, but upheld the consideration of race in admitting decisions.)

No One Gets Away Without a Vaccination

After receiving her BSN degree, Buada worked as one of only two Spanish-fluent public health nurses at the Monterey County Health Department (MCHD). In a van serving as a mobile clinic, she and a pediatrician brought vaccinations and school-entry well-child exams to children in migrant labor camps around the county. She says, “Our goal was to make sure at least 90 percent had all their shots and developmental exams by first grade. I prided myself in making sure that not a kid got away without all their immunizations.”

Public health nursing functions included handling cases involving child abuse and neglect. She says, “It was the thing I liked least. I was 23 at the time, and at that age, you just don’t know how to handle that, especially with no parenting experience.”

A Clinic for Farmworkers

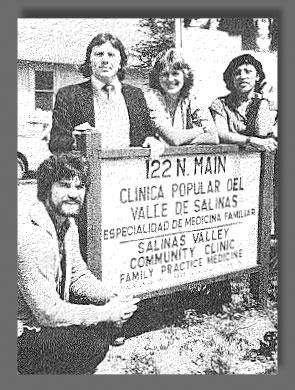

Buada (far right) at the Clinica Popular del Valle de Salinas, 1982 In 1978, while working for the MCHD, Buada learned that the UFW-funded Salinas clinic, where she had first worked in health care, had closed. She got together with nurses from the closed UFW clinic to develop a community-owned health center in Salinas. The idea sprang from a trip to study programs in Cuba, where she met officials from the California State Office of Rural Health and the California Rural Indian Health Board who were part of Governor Jerry Brown’s (first term) Primary Care Clinics Advisory Committee.

Buada (far right) at the Clinica Popular del Valle de Salinas, 1982 In 1978, while working for the MCHD, Buada learned that the UFW-funded Salinas clinic, where she had first worked in health care, had closed. She got together with nurses from the closed UFW clinic to develop a community-owned health center in Salinas. The idea sprang from a trip to study programs in Cuba, where she met officials from the California State Office of Rural Health and the California Rural Indian Health Board who were part of Governor Jerry Brown’s (first term) Primary Care Clinics Advisory Committee.

After the Cuban visit, Buada was invited to join the committee, where she picked the brains of the clinic directors on it for information on getting funding to start clinics for low-income populations. Armed with their advice, Buada and her colleagues got to work.

“We raised money, we found a house, and we renovated it with volunteers who had helped build the union’s clinic in Delano,” she says. The group landed a $250,000 Farmworker Health Center grant from the Office of Rural Health, enabling them to equip and staff the clinic with one nurse practitioner, one physician, plus recruits from a job training program. The Clinica Popular del Valle de Salinas opened its doors in 1980, with Buada as executive director. The name of this clinic has since been changed to Clinica de Salud del Valle de Salinas; it continues to thrive to this day.

“It was an adventure,” says Buada, who had never run a business before. “When I set out, everyone said, ‘You can’t do this.’ I said, ‘Give me a dare and watch me.’” Her approach was to find people with the knowledge and skills she lacked to teach her. One of the carpenters taught her to do the scale drawings the clinic needed to submit to the city for approval of the building sign. The city planner initially rejected the plan, she says, telling her, “You’re not a contractor or an architect; you aren’t anything. You can’t send this in.” Buada took the issue to a county hearing, where the judge overruled the planner.

After three years, Buada left to help turn around a foundering clinic in Watsonville that had lost its license. She spent six months working with the clinic’s board chair, re-evaluating processes, restaffing it and ultimately earning back its license.

Consulting on Clinic Management

As Buada acquired a growing reputation for pragmatic and transformative clinic management, a consultant working with federally funded health centers across the U.S. invited Buada to join his firm to help with strategic planning and budgeting at a time when the federal government was making budget cuts and asking clinics to develop more diverse sources of funding. Again, she found herself learning on the job about strategic planning, researching everything she could by reading magazines like Medical Economics and Healthcare Financial Management at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health library.

After two years at the consulting firm Rosenberg and Associates, during which she helped create successful financial models for urban and rural clinics to transform their health care delivery systems, Buada left to work independently as a consultant doing board training and strategic and operational planning for health centers across the West.

Stabilizing a Primary Care Clinic in Berkeley

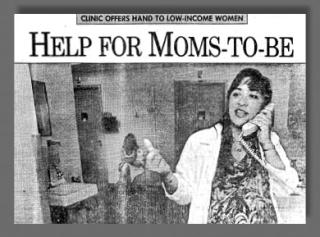

Berkeley Primary Care Access Clinic, 1991 In 1988, at the urging of colleagues, Buada entered the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, her tuition paid for by a federal program for minority nurses who wanted to pursue graduate degrees. After earning her master’s of public health two years later, Buada was recruited by Berkeley’s public health officer at the time, physician Carmen Nevarez, to help start the Berkeley Primary Care Access Clinic for low-income patients at the Herrick Campus of Alta Bates Medical Center (now Alta Bates Summit Medical Center).

Berkeley Primary Care Access Clinic, 1991 In 1988, at the urging of colleagues, Buada entered the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, her tuition paid for by a federal program for minority nurses who wanted to pursue graduate degrees. After earning her master’s of public health two years later, Buada was recruited by Berkeley’s public health officer at the time, physician Carmen Nevarez, to help start the Berkeley Primary Care Access Clinic for low-income patients at the Herrick Campus of Alta Bates Medical Center (now Alta Bates Summit Medical Center).

There was a lot of work to be done. “I did a lot of remodel designs and laid out the floor plan, but there was no way we could pay for it up front,” Buada says. The clinic signed an agreement under which the hospital would lend the money for the renovations, to be paid back over seven years. To convince the hospital to agree to the arrangement, Buada worked with a board member to demonstrate that the clinic could help the hospital’s bottom line by providing care to hospital patients ready for discharge who had no doctor of record – mostly low-income or Medi-Cal patients – who, by law, would otherwise have to stay in the hospital, which would receive little or no reimbursement for those inpatient days.

Alta Bates ended up writing off the clinic’s $250,000 construction loan and supporting the health center annually with $250,000 in grants and in-kind services. “It was a really good example of a public-private partnership,” says Buada. “In some ways it became a model for a lot of other organizations working with nonprofit community hospitals.”

During her six years with the Berkeley Primary Care Access Clinic, Buada shepherded it through a merger with Over 60 Health Center and West Berkeley Health Center to form LifeLong Medical Care, which has since grown to provide care to more than 40,000 people across Alameda, Contra Costa and Marin counties each year.

Expanding Care in East Palo Alto

In 1997, Buada left LifeLong Medical to become executive director of the California Institute for Rural Health Management’s program to develop integrated health systems in five rural California counties under a variety of managed care models. When the project ended, due to lack of enough patient volume to keep insurers interested, Buada intended to go back to consulting, but a friend sent out a distress signal that she couldn’t ignore.

A community clinic in East Palo Alto, which Buada had helped organize as a consultant, had run into trouble during its first year in operation. Buada says, “They called me and said, ‘Just come down for three months and teach [the staff] everything you know.’ That was November 2002, and I’ve been there ever since.”

Buada became interim, then permanent, CEO of the clinic, the Ravenswood Family Health Center. Under her leadership, the center has pursued a program of steady growth and expansion, and now operates with a budget of $28 million to serve more than 15,000 patients per year, most of whom are low- or very low-income.

Since its inception as a basic adult and pediatric clinic, Ravenswood has added desperately needed services such as integrated behavioral health, women’s health, optometry, imaging, pharmacy and dentistry, thanks to innovative fundraising and careful leveraging of federally available funding. Buada says, “I’m a risk-taker. My attitude has always been, we do the right thing, and the money will come.”

A partnership with Palo Alto Medical Foundation has allowed them to offer screening mammography, ultrasound and general X-ray services. Last year, they opened a new $39 million facility, the result of a massive fundraising effort combined with a funding mechanism known as New Markets Tax Credit financing, which is intended to encourage investment in low-income communities by offering tax credit incentives to federally certified investors in community development projects.

Buada’s contributions to the well-being of the underserved and disadvantaged were recognized in early 2016 when she was among eight nominees for the San Francisco Chronicle’s Visionary of the Year Award, honoring leaders who “strive to make the world a better place and drive social and economic change by employing new, innovative business models and practices.” At an honorary dinner in May 2016, she also received the John W. Gardner Leadership Award from the American Leadership Forum – Silicon Valley.

Creating Opportunity in the Community

When asked about her proudest accomplishment, Buada doesn’t offer the health care she’s helped provide to tens of thousands of California’s poorest. Instead, it’s the empowerment of young women of color through employment in important, meaningful work with the organizations she’s led.

“These are women who have come from very challenging circumstances, and they come into our organization and gain skills and a more confident sense of themselves, so they can look towards moving on into nursing, higher education or managerial positions,” Buada says.

To Buada, such empowerment is integral to improving the well-being of the community. She likes the synergy of creating opportunity while improving public health. She says, “The ability to provide jobs at all levels in a community like ours and have a health center that represents the people in terms of culture, color, language and the perspective of our patients: All of that is what I’m proud of.”

Each year, UC San Francisco (UCSF) School of Nursing is ranked among the top graduate schools in the nation.