Sally Rankin delivers the 35th Helen Nahm Research Lecture (photo by Elisabeth Fall).

The Heart of the Matter: From Families and Heart Disease to the Warm Heart of Africa

On May 28, Sally Rankin, professor emerita and past department chair, interim dean and MacArthur Chair for Global Health Nursing in the UC San Francisco School of Nursing, delivered the 35th Helen Nahm Research Lecture to an audience of clinicians, researchers and other colleagues at the School’s Parnassus campus.

Rankin’s lecture traced the trajectory of a distinguished career that has taken her from social work in upstate New York to cardiovascular nursing and research in Massachusetts and California and, ultimately, to Malawi, where she works to improve the health of families and build the nursing workforce. At the heart of all of her work, she said, is recognizing that “family matters.”

Becoming a Nurse

Rankin’s choice of career was deeply influenced by her parents. She called her mother “a feminist at heart” who would have disavowed the term. Her father, a World War II Navy pilot, urged her to pursue a career in health care. During her first post-university job as a social worker in upstate New York, Rankin decided they were right.

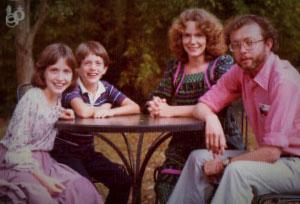

Sally Rankin with her husband, William, and children in Durham, North Carolina, in 1978 “While making home visits to clients living in Appalachia, I realized they needed health care more than they needed me,” she said. She took her nursing degree and, in 1978, returned to school at Duke University to pursue a master’s in nursing, where she was introduced to family systems theory, which suggests that individuals can only be understood in the context of the family. This resonated with Rankin, the eldest of three sisters, and became a guiding principle in her work.

Sally Rankin with her husband, William, and children in Durham, North Carolina, in 1978 “While making home visits to clients living in Appalachia, I realized they needed health care more than they needed me,” she said. She took her nursing degree and, in 1978, returned to school at Duke University to pursue a master’s in nursing, where she was introduced to family systems theory, which suggests that individuals can only be understood in the context of the family. This resonated with Rankin, the eldest of three sisters, and became a guiding principle in her work.

Looking at Disease Through the Lens of Family

In 1984, Rankin and her family moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, where she became part of the first group of nurses to enter the UC San Francisco School of Nursing’s PhD program. Her dissertation looked at the effects of gender, age and caregiving in cardiovascular disease. She found that there were differences between men and women in how disease presents and how patients recover, and that families had an influence on these differences.

After finishing her PhD, Rankin became director of the UCSF Diabetes Teaching Center, helping families learn to manage the condition. The diversity of the area’s population gave her many research ideas, including what ultimately became a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded study that allowed Rankin to examine how Chinese Americans’ views on health and illness influenced patients’ management of diabetes. The study revealed high levels of depression and poor quality of life, possibly related to poverty and the marginalization of immigrants. Again, said Rankin, she was struck by how important families were in the management of the condition.

Cardiac Coaches in Boston and San Francisco

A 1993 move back to Boston afforded Rankin the chance to take up cardiovascular research once again. In a pair of multiyear studies conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital, UCSF, Stanford and UC Davis, she and her colleagues looked at interventions to improve health outcomes of older, unpartnered patients who had had myocardial infarctions (MI) or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABS).

“We used a peer coaching model (‘Cardiac Coaches’), where participants who had had either MI or CABS acted as advisors to participants who had just been released from the hospital (after MI or CABS),” she said. Coaches also had an intervention nurse available to advise them on difficult cases.

The researchers found that there were significantly fewer rehospitalizations, increased treatment adherence and greater participation in cardiac rehabilitation programs among those in the intervention group than among those in the standard care (without peer/nurse advisors) group.

Combating HIV in the “Warm Heart of Africa”

Family ties were to play a key role in Rankin’s later career path, which changed direction dramatically in 2000.

That was the year Rankin’s husband, William, an Episcopal clergyman and former dean and professor of Christian ethics at Cambridge’s Episcopal Divinity School, became increasingly concerned about the HIV/AIDS epidemic’s devastating impact on sub-Saharan Africa. With his friend, UCSF neurosurgeon Charles Wilson, he founded the Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance (GAIA). The group focused its efforts on Malawi, a country particularly hard hit by the epidemic.

“I had never heard of Malawi before my first trip there,” said Rankin. She found a people in desperate need. “The population of Malawi was 13 million, and the HIV prevalence was variously reported as 20 to 38 percent. More than 500,000 children were orphaned because of HIV. There were no antiretrovirals (ARVs) available to about 99 percent of the population, so the diagnosis of HIV was a death sentence.”

Moreover, she said, socioeconomic and cultural conditions made preventing infections extremely difficult, particularly among women and girls. Orphaned girls often turned to transactional sex to support younger siblings. In some tribes, cultural practices, such as female genital mutilation, increased the rate of HIV exposure in women and girls. In tribes that practiced “widow inheritance,” a husband’s family inherited his property at his death, leaving women and children economically vulnerable.

Partnering with Religious Organizations to Combat HIV/AIDS

Rankin realized that improving the lives of women and girls would be essential in improving the health of the entire population. She conducted three focus groups and individual interviews with Malawian women to find out what familial, cultural and religious influences contributed to HIV. She found that women were disenfranchised in many ways, including limited educational and employment opportunities. “Women do the donkey work,” she said, quoting one of the study participants.

“It became increasingly clear that religious leaders and members of their organizations could provide leadership in HIV prevention,” Rankin said. Studies have shown that religious commitment is associated with improved knowledge of HIV and lower rates of some sexual risk-taking behaviors. Moreover, in Malawi, religious organizations provided much of the care to people with HIV and their families and were a key support of the country’s health care system.

The Rankin family celebrates after the lecture (photo by Elisabeth Fall). In collaboration with GAIA, Rankin and her colleagues secured a multiyear grant from the NIH to examine how best to harness the power of churches and mosques to reduce stigma and promote HIV prevention and care. They interviewed leaders and members across faith groups to examine attitudes and investigate how ideas and innovations moved through the groups’ religious hierarchies.

The Rankin family celebrates after the lecture (photo by Elisabeth Fall). In collaboration with GAIA, Rankin and her colleagues secured a multiyear grant from the NIH to examine how best to harness the power of churches and mosques to reduce stigma and promote HIV prevention and care. They interviewed leaders and members across faith groups to examine attitudes and investigate how ideas and innovations moved through the groups’ religious hierarchies.

Key findings included that religious teaching, cultural practices and stigmatizing attitudes contributed to HIV infection rates and prevented faith-based organizations from providing effective care to people with HIV. Many of these challenges disproportionately affected women, who are were powerless to affect their husbands’ sexual behavior. They presented these findings to religious leaders in a pair of meetings, and GAIA continues to work with religious organizations to find culturally appropriate ways to promote HIV prevention.

More Nurses, Better Health

Nurses are the backbone of Malawi’s health care system, and over the past several years, Rankin has focused on building nursing capacity there. With GAIA, she has worked to educate nurses with funding from USAID (United States Agency for International Development), often bringing faculty and students from UCSF to teach and learn. She has also looked for opportunities to connect the School with other organizations working to increase nursing capacity in the developing world.

The 2014 establishment of the Center for Global Health at the School has expanded that aim. Rankin was founder of the center, which works to increase collaboration across the school and among international nursing programs as part of an effort to prepare a global nursing workforce to deliver care, particularly in marginalized populations

“Geography is destiny,” said Rankin, summing up her view of the importance of taking a global approach to health care, and she emphasized the idea of a global family: “Those of us who have opportunity are privileged to be sisters and brothers to those in need.”