Understanding Pediatric Acute Care Nursing: The Patients’ Perspective

The transfer in February of more than 130 patients – mostly children – from UCSF Medical Center at Parnassus to the trio of new UCSF hospitals at Mission Bay was by all accounts a well-executed move by an entire organization.

It was also an exaggerated example of a care transition and of the need for skilled clinicians – often acute care nurses, clinical nurse specialists or nurse practitioners – trained to ensure coordinated, continuous care as patients move between different locations or different levels of care.

Transitional care is a hot topic these days due to its emphasis in the Affordable Care Act, but, of course, overseeing transitions is only one of many clinical roles for acute care nurses. Others include patient monitoring, symptom management, patient education, family support, patient advocacy and communication. Acute care nurse practitioners (NPs) also diagnose and treat patients.

All of these roles are crucial for patients’ sustained recovery from illness and reintegration into their lives when they leave clinical settings. All demand training and high-level thinking. Yet outside of the nursing world, these roles are often misunderstood, and downplayed in vaguely patronizing ways, such as stories about nurses with hearts of gold, as though compassion – important as it is – were the only skill needed to perform the job. Such portrayals can be a source of frustration for nurses, leading to the emergence of groups like The Truth About Nursing and The American Nurse Project.

But some nurses take refuge in the knowledge that most patients and families who have suffered a serious health crisis know the role that nurses play. Often, these families have remarkable insights into how their lives might have been different if not for the work of expert nurses.

Managing Pain

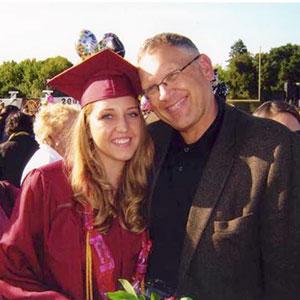

Katie Blue and Amanda Wallis Consider Amanda Wallis and her daughter Kathleen (Katie) Blue. Now 24, Katie was born with a congenital heart defect – a double-inlet single ventricle – that required a series of complicated surgeries by a highly skilled surgeon to address. Though it was almost a quarter century ago, Amanda remembers vividly sitting with her intubated infant in the aftermath of the first corrective operation and observing Linda Roan (MS, 1986), a pediatric intensive care nurse at UCSF Medical Center.

Katie Blue and Amanda Wallis Consider Amanda Wallis and her daughter Kathleen (Katie) Blue. Now 24, Katie was born with a congenital heart defect – a double-inlet single ventricle – that required a series of complicated surgeries by a highly skilled surgeon to address. Though it was almost a quarter century ago, Amanda remembers vividly sitting with her intubated infant in the aftermath of the first corrective operation and observing Linda Roan (MS, 1986), a pediatric intensive care nurse at UCSF Medical Center.

“The procedure Katie underwent basically rejiggers your circulatory system, and success or failure depends on the child’s reaction in the days after, so constant monitoring and observation are very important,” says Amanda today. “Linda and the other nurses were with Katie all the time, and Linda, in particular, knew Katie – knew without looking at the chart the amount of sedation and pain medication Katie needed to keep her comfortable while she was restricted to bed with all those painful chest tubes.”

The respect Roan engendered went far beyond Katie’s mother. When Katie’s cardiac surgeon would round, he would always ask Roan for her clear, concise updates on Katie’s status before looking at any charts.

Amanda also recalls that Roan made sure residents on rotation had a detailed understanding of baby Katie’s needs, in particular that Katie would need extra sedation when it came time to extubate. Roan asked that the residents perform the extubation during her shift so she could ensure the infant was comfortable.

When the residents ignored these instructions and the child’s stressful reaction forced them to reintubate, Amanda was there. “I remember thinking, ‘This is not just about medical training; it’s about knowing the patient and their needs’ – and that’s what nurses do,” says Amanda.

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” says Roan. “Katie’s family was exceptional; they were there all the time, and they understood how pivotal nurses are for families and patients because we too are there all the time and get to know our patients thoroughly; our physical assessment is a lot more than looking at monitors.”

She adds that helping infants with congenital heart defects like Katie recover is a team effort among the clinical providers and the family. It’s essential, says Roan, that every member assertively bring his or her expertise to that effort.

Linda Roan (left) and Mary Lynch “As nurses, because we know our patients best, we have to be their strong advocates,” she says. “We need to bring our evidence-based practice into the room and make sure we get heard. I’m like a mama bear in that way; to work in a cardiac ICU, you better have a strong sense of yourself.”

Linda Roan (left) and Mary Lynch “As nurses, because we know our patients best, we have to be their strong advocates,” she says. “We need to bring our evidence-based practice into the room and make sure we get heard. I’m like a mama bear in that way; to work in a cardiac ICU, you better have a strong sense of yourself.”

Ten years later, when Katie was in the hospital recovering from follow-up surgery for the heart defect, another nurse would be a lifesaving advocate when she noticed that something was not quite right.

“She couldn’t put her finger on it, but she called the ICU doctor, and two minutes later, Katie crashed,” says Amanda. “It was another lesson in understanding how important nurses are.”

“Those types of stories illustrate why we prepare nurses to be critical thinkers – to size up a situation in a clinical area and identify a problem,” says acute care pediatric nurse practitioner Mary Lynch, who runs UC San Francisco School of Nursing’s Acute Care Pediatric Nurse Practitioner program. “It’s a different domain than the physicians’, but equally important for the health of patients.”

Transforming a Family’s Life

Randall (Randy) Lipps went through a similar experience with his daughter Sarah, now 25. When Sarah was born at a South Bay hospital, she was laboring to breathe. After a series of escalating interventions, the newborn was sent to UCSF.

Still, Sarah continued to go downhill, and no one knew why for sure. The doctors ordered tests and would explain to the Lipps family where things stood, but Lipps and his wife were trying to take it all in while under considerable emotional stress. It was the nurses, says Lipps, who translated the information.

“They put it in a framework that a layperson could understand,” he says. “When an alarm went off, they let me know whether I should panic – it was a great gift to be allowed into the middle of their very complex clinical world. They have a perspective that is more than just looking at charts and numbers, and I found that very comforting.”

Having seen hundreds of cases, the nurses assured him that Sarah’s problem – eventually diagnosed as respiratory distress syndrome from underdeveloped lungs – was curable. And they were right.

Transitions, Transitions, Transitions

Sarah and Randy Lipps Knowledge and comfort were also critical when Sarah had to be moved. The first time was from the South Bay hospital to UCSF.

Sarah and Randy Lipps Knowledge and comfort were also critical when Sarah had to be moved. The first time was from the South Bay hospital to UCSF.

“I remember coming into the hospital – we were transferred in by ambulance at 2 a.m. – but we didn’t know anything,” says Lipps. “Both the doctor and nurse came out to talk to us, but it was the nurses who were with us for the next 12 hours; they were the people who in a very short amount of time we knew we could trust. They knew what to do and they cared.”

Similarly, when the Lipps family brought Sarah home, the nurses patiently explained all of the potential scenarios and made sure that Lipps knew he could call them anytime, day or night.

Katie Blue dealt with another type of transition as she prepared to head off to college and needed to understand how to manage her condition while far away from her long-term care providers. “I spent a lot of time talking with my cardiac nurse practitioner, Valerie [Bosco], the one person who has been consistently with me,” says Katie. “There are always so many questions: whether I’ll be able to carry children eventually, exercise tolerance, all of these things that come with having a heart condition.”

“It’s where we come in,” says Bosco, a PhD-prepared clinical nurse specialist who received her MS from the School in 1991. “I am basically the eyes and ears for the cardiologists, and I do a lot of teaching: in person, on the phone, by email. It’s a team approach, but I make myself as available as I can for the patients – especially for [those who have undergone a Fontan procedure, as Katie did]. They ask about birth control or medication, or they need me to be in touch with a new physician if they move.”

Bosco adds that in all of these interactions, it’s important to not just talk, but to cultivate the art of listening. “You have to meet patients where they are; you can’t just rush in there and tell them what they need to be doing,” she says. “We have to discover what we need to be doing together, so they actually have the will and understanding to get it done.”

Working with Families

Especially in pediatric acute care settings, another key role that combines clinical knowledge with creativity and compassion is working with families.

Lipps remembers asking, somewhat fearfully, if he could hold the infant Sarah despite all the tubes and equipment she was hooked into. “The nurse said, ‘You should hold her,’ and she undid all of this rigging to let me hold her for maybe five or 10 minutes,” he says. “I’m not sure the doctor would have appreciated that, but it meant the world to me.”

Amanda Wallis also remembers the nurses insisting she hold Katie when she was an infant. “I really hadn’t had a chance to hold Katie since she had been born, and their enabling me to do that was so wonderful,” says Amanda.

Inspired by the Skills, Not Just the Caring

In the end, Lipps was so moved by the direct patient care that nurses perform – “God’s work,” he calls it – that he formed what has become a publicly traded company that makes products to ease workflows and better manage supplies and medications, so clinicians, particularly nurses, can give their full attention to administering care.

“Nearly everything people do in a hospital – the doctors, pharmacists, lab techs – is executed through the hands of nurses,” says Lipps. “They do most of the actual touching, they administer medications, and they provide the avenues for healing – they are the physical presence that moves things along.”