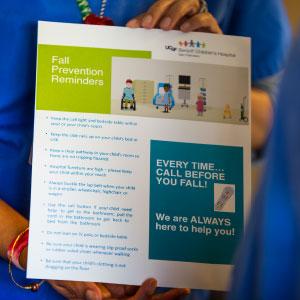

Barbette Murphy (right) introduces a patient/parent educational brochure about preventing falls to Hospital Unit Service Coordinator Yolanda Jackson (photos by Elisabeth Fall).

Predicting and Preventing Pediatric Falls in the Hospital

“Children are not little adults,” says June Shu-Ling Chan, director of Nursing Practice, Patient Experience and Special Projects at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital San Francisco.

That aphorism is the driving idea behind a collaborative research project that teams clinical and nursing administration staff at the hospital with nurse researchers at UC San Francisco School of Nursing. The goal is to evaluate and improve a clinical tool to predict which children are at risk for falling during a hospital stay and, ultimately, to prevent falls among hospitalized children. Initial findings from the study were published in the March 2017 issue of the International Journal of Nursing Studies.

Patient falls are a significant safety issue in hospitals, with research suggesting that between 700,000 and one million patients suffer one or more falls during a hospital stay each year in the United States; 30 percent to 35 percent of those falls result in injury.

There’s been relatively little research on pediatric falls, but what exists suggests that children fall less often – with an estimated 0.56 to 2.19 falls per 1,000 patient days, versus 1.4 to 17.9 for adults – but that they are also at risk for injury, from minor bumps and bruises to serious head injury. Up to one-quarter of falls in toddlers, for example, may result in concussion.

Different Reasons for Pediatric Falls

In addition to fall causes that also affect hospitalized adults, such as medication side effects or muscle weakness from inactivity, normal developmental changes can increase the risk of falls in children. Learning to walk, learning to use the toilet, and impulsivity related to development can raise the chances that a child will fall. Younger children may run through halls or bounce on beds, while teens, who typically want privacy, are at greater risk because they often resist the requirements that someone remain with them while they use the toilet or shower and are reluctant to ask for help.

Children can also become hypoglycemic or dehydrated quickly, an important factor in patients who may spend hours without eating or drinking prior to a procedure.

“Pediatric patients have dynamic changes. You really need an individualized plan for falls prevention – it isn’t one size fits all,” says pediatric nurse practitioner Barbette Murphy (MS ’13), a clinical nurse specialist in the hospital’s pediatric medical/surgical care unit who has been leading clinical efforts related to falls prevention.

Adapting a Risk Assessment Tool to Predict Children’s Falls

In 2005, The Joint Commission (which accredits hospitals in the U.S.) began requiring hospitals to have a falls prevention program in place for all hospitalized patients. UCSF Medical Center used a tool known as the Schmid Fall Risk Assessment in its adult falls prevention program, but Maureen Buick, then the medical center’s director of Nursing Education and Performance Improvement, found that, while there were several tools available for assessing adult patients, none of them had been validated as effective in a pediatric population. She and a group of nursing colleagues decided to adapt the Schmid tool for use in children hospitalized at the medical center.

They called the tool the “Little Schmidy.” Like the Schmid, the Little Schmidy assigns risk scores based on several criteria, including fall history, medications, mobility, mental activity and elimination status (how often the patient needs to use the toilet and whether the patient needs assistance in using the toilet). The medical center adopted it. Soon, other hospitals across the bay (Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, which is now UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland) and across the ocean (Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia) began using it in their falls prevention programs, although it had never been formally studied for reliability. Buick was eager to change that. In 2011, she approached nurse researcher Linda Franck from the School to suggest a collaboration between the hospital and the School that would scientifically validate the tool.

Validation is important, says Carrie Meer (MS ’04), director of Nursing Performance Improvement and one of the collaborators on the project, because making good decisions about clinical care requires accurate data. “If [your assessment tool] isn’t measuring what you think you’re measuring, how valuable is the information? Should you be acting on it if it’s not reliable?” she asks.

Testing the Little Schmidy

A team of clinicians from the hospital, including Buick, Chan, Meer, Murphy and nurse Suzanne Ezrre, with researchers from the School, including Franck, biostatistician Bruce Cooper and research specialist Caryl Gay, collaborated to examine the tool for sensitivity and specificity in predicting pediatric falls. Because they are a relatively rare event, it can take a long period of study to gather enough data to make accurate inferences, but thanks to the hospital’s adoption of an electronic medical records (EMR) system, the team was able to compile a robust set of 151,000 data points for more than 5,000 patients over a five-year period.

“With the level of documentation available from the EMR, we were able to do a much more sophisticated analysis looking across hospitalizations, across shifts and at the influence of different patient characteristics,” says Franck.

The team looked to see if there was a relationship between Little Schmidy risk scores and falls, and to determine which elements of the tool contributed to its predictive accuracy. They found that, while the Little Schmidy performed as well as or better than other tools, some elements weren’t helpful in identifying patients at risk for falls, such as evaluating mental activity or cognitive impairment – an important fall predictor in adults, but less so in children.

Revising the Little Schmidy

Based on their findings, the team suggested a number of changes. These included streamlining the Little Schmidy to use binary (0 or 1, corresponding with “no” or “yes”) scoring for all items rather than more detailed numerical scoring, which simplified the tool and increased consistency across users.

Streamlining the tool will also help with integrating it into the EMR, which could yield benefits in both current patient care and research, says Franck. “It could give nurses better information and alert them to fall risk, the way the system now alerts them to a drug allergy or medication interaction.” EMR integration would also give researchers the ability to evaluate large amounts of aggregate data and identify trends related to falls on an ongoing basis, allowing clinicians to innovate and track the effects of changes to protocols in a more agile fashion.

Another aim of the project was to take a close look at patients who fell, to identify patterns and patient characteristics that might be used to better predict falls. The team found that older children were at higher risk, as were children with neurological disorders and those who had had more than one hospitalization during the study period. Moreover, they found, about one-third of falls happened when patients fell out of bed.

Improving Falls Prediction in the Future

UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital San Francisco’s pediatric falls prevention program includes working with families to ensure they understand the risk of falls and how to help prevent them. Chan, Meer and Murphy are working with nursing leadership and staff at the hospital to implement the streamlined Little Schmidy tool and make improvements in the hospital’s falls prevention protocol based on the study’s findings.

UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital San Francisco’s pediatric falls prevention program includes working with families to ensure they understand the risk of falls and how to help prevent them. Chan, Meer and Murphy are working with nursing leadership and staff at the hospital to implement the streamlined Little Schmidy tool and make improvements in the hospital’s falls prevention protocol based on the study’s findings.

Those findings point the way for further research and give clinicians further direction on where to focus interventions to prevent falls. Franck hopes to pursue EMR integration and to extend the researcher-clinician collaboration to other children’s hospitals in the region – and, ultimately, across the country.

Of course, she notes, a risk score alone can’t predict falls. In the end, it takes a team approach, with rigorous, ongoing research allied with clinical judgment and consideration of patients’ individual needs, to inform and improve practice and make the hospital a safer place for patients.