Strategies to retain nurses, alleviate stress and significant policy changes may be necessary to combat the U.S. nursing shortage.

The Nursing Shortage is a National Problem. How We Can Solve It.

The U.S. has faced periodic nursing shortages over the past century, but the current national shortage has been especially severe and may prove to be persistent.

Faculty at the UCSF School of Nursing are exploring the root causes of the national nursing shortage and formulating potential solutions to address this alarming trend.

What is Causing the Nursing Shortage?

There are approximately 3.9 million registered nurses (RNs) in the U.S., and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projects that more than 500,000 RNs will retire by 2022. Accounting in large part for replacing those retirees as well as other factors, the BLS estimates 1.1 million new RNs will be needed to prevent a shortage.

Joanne Spetz The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the need for new RN graduates as older nurses retire sooner, especially in California. An August 2021 report co-authored by Joanne Spetz, professor at the School of Nursing and director of UCSF’s Philip R. Lee Institute of Health Policy Studies, found that the percentage of California RNs ages 55 to 64 planning to retire or quit in the next two years more than doubled from 11.4% in 2018 to 25.2% in 2020.

Joanne Spetz The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the need for new RN graduates as older nurses retire sooner, especially in California. An August 2021 report co-authored by Joanne Spetz, professor at the School of Nursing and director of UCSF’s Philip R. Lee Institute of Health Policy Studies, found that the percentage of California RNs ages 55 to 64 planning to retire or quit in the next two years more than doubled from 11.4% in 2018 to 25.2% in 2020.

And although the percentage of RNs ages 65 and older who plan to retire or quit in the next two years did not increase significantly from 2018 to 2020, Spetz notes that the employment rate for this age group decreased substantially, “suggesting that many RNs in this age group who might have been planning to retire already did so.”

“We’ve been preparing for those retirements,” Spetz said, “but it looks like a big chunk of them is happening a lot more precipitously than we expected.”

Along with the aging nurse workforce, the stress associated with nursing is resulting in burnout. Nurse turnover rates are as high as 37 percent, depending on geographic area and specialty.

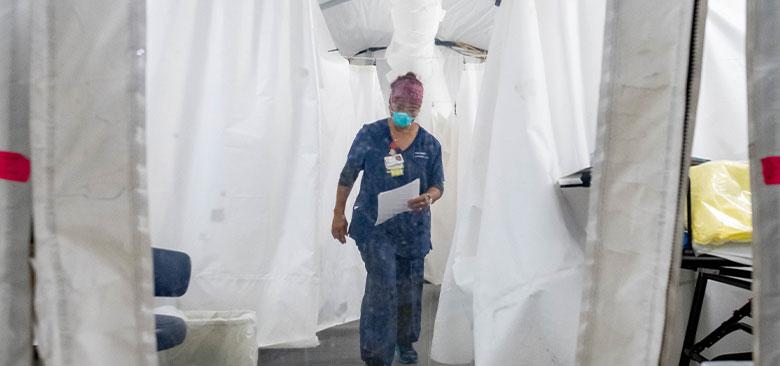

“During the initial crisis of COVID in the U.S., the role of nurses caring for patients, many of whom were dying in hospitals, increased nursing visibility,” said Carol Dawson-Rose, professor at the School of Nursing. “But the sheer stress and numbers of people diagnosed with COVID is exhausting the nursing workforce and the visibility of nurses caring for people with COVID has diminished.”

In addition, educating the next generation of nurses is becoming increasingly difficult as nursing schools are dealing with faculty shortages, difficulty securing clinical opportunities for students and restrictive state policies, resulting in decreased enrollment. Spetz’s report also cited concerns about safety in clinical rotations and the challenges in shifting to online learning as additional reasons for enrollment reductions.

If this shortage is not addressed, patients may experience more negative health outcomes. Studies, such as Spetz's 2011 article in Medical Care, show that higher nurse staffing protected patients from poor outcomes.

Retaining and Investing in Nurses

To maintain high-quality care for patients, health care organizations must find innovative ways to retain nurses, School of Nursing experts say.

Many nurses are becoming “travel nurses,” leaving their full-time positions to accept temporary, contract-based assignments at hospitals across the nation, often for higher pay.

While paying nurses higher salaries may increase retention in health care organizations in the short term, non-financial incentives, such as educational and development courses, advanced certification and  Carol Dawson-Rose leadership opportunities, are important as well, said Dawson-Rose. Health care systems must provide ample time for nurses to pursue these development opportunities, she said.

Carol Dawson-Rose leadership opportunities, are important as well, said Dawson-Rose. Health care systems must provide ample time for nurses to pursue these development opportunities, she said.

“When we go through these cycles of shortages, nurses delay their education,” Dawson-Rose said. “Their employers who are pressured by the shortage of staff aren’t as lenient with schedule or assignment changes that would take time away from work for education that will result in an advanced degree or leadership training. That needs to change.”

Another necessary change is alleviating stress, said Andrew Penn, associate professor at the School of Nursing and a psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner. Nurses have witnessed and endured significant trauma, especially during the pandemic. A recent study found female nurses were twice as likely to die by suicide than the general population. What’s more alarming, Penn notes, is that the data was gathered before the pandemic.

While some have suggested that nurses seek out meditation or yoga for stress relief, Penn says this notion shifts the responsibility for burnout to the individual.

“It’s a form of victim-blaming, because it attributes the clinician’s exhaustion and burnout to something the employee failed to do and absolves the employer or the larger health care industry from culpability,” Penn explained.

Andrew Penn Instead, Penn recommends health systems consider reasonable productivity expectations for clinicians, in addition to establishing meaningful wellness programs to more proactively prevent and address nurse stress and burnout.

Andrew Penn Instead, Penn recommends health systems consider reasonable productivity expectations for clinicians, in addition to establishing meaningful wellness programs to more proactively prevent and address nurse stress and burnout.

Academic institutions and professional organizations may need to innovate as well. The California Board of Registered Nursing (BRN) caps enrollment in the state’s nursing schools because of limited clinical opportunities for students, restricting thousands of potential nurses from matriculating into nursing programs.

Solving this issue requires policy or “structural-level solutions,” said Dawson-Rose. The California BRN removing the cap on enrollment for schools of nursing would be a significant step forward. Enrollment planning by the BRN must be linked to the forecasted supply of nurses that California needs, she said. Large health systems in California must also step forward to increase the number of clinical placement spots to meet the needs of students who must achieve competency through clinical experience and training. Creating incentives to increase the number of clinical preceptors for students is another avenue health systems could support, Dawson-Rose said.

Other creative solutions emerged during the pandemic, such as when UCSF and its School of Nursing facilitated clinical opportunities like Operation Safer Ground and UCSF’s COVID Patient Hotline to  Natalie Wilson enhance the clinical training of its students while responding to immediate local needs. Partnering with public health entities and health care systems to create similar clinical experiences could reinvigorate nurses and enhance their skill set, said Natalie Wilson, assistant professor.

Natalie Wilson enhance the clinical training of its students while responding to immediate local needs. Partnering with public health entities and health care systems to create similar clinical experiences could reinvigorate nurses and enhance their skill set, said Natalie Wilson, assistant professor.

“What nursing is good at is seeing where the gap is and developing interventions to meet that gap. For example, students going to Operation Safer Ground are not only working on their skills, but they’re meeting the needs of the population there,” said Wilson, who mentored nurse practitioner students at that project.

Added Spetz: “We need to keep investing in nursing education capacity. And employers need to invest in new graduates. Those nurses who are retiring are experts and you can’t have a new graduate instantly go into those jobs. Employers are going to have to help develop the skills of new graduates so we’re able to maintain the workforce.”