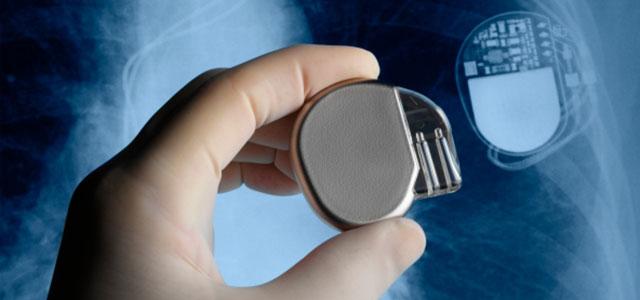

An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

Living for a Shock: Listening to Patients with Implantable Defibrillators

One of Cindy Wojtecki’s most memorable patients died before he reached her emergency department.

Wojtecki was working as a charge nurse and was enlisted to help prepare the patient’s body so that his family could say good-bye. When the family came into the room, the patient’s implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) discharged, and the body of their deceased loved one unexpectedly jerked in response.

“It had not been deactivated,” says Wojtecki. “I was as startled as the family; it was horrible.”

This memory speaks symbolically to what Wojtecki found in completing her doctoral research at UC San Francisco School of Nursing: there is a disturbing lack of awareness among clinicians, patients and families about what it is like to live with one of these devices. A nurse for more than 30 years, who has served in the emergency department, as a medical/surgical clinical nurse specialist and as chair of the ethics committee at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Syracuse, New York, Wojtecki received her PhD in 2011. Her work focused on understanding the impact on older adults of living with an ICD.

Explosive Growth of a New Technology

An ICD is a lifesaving device for patients with ventricular arrhythmia – a condition in which the electrical impulses within the heart cause it to beat irregularly – who are at risk for sudden cardiac arrest. The ICD is surgically implanted and programmed to recognize a life-threatening arrhythmia and deliver a shock that corrects the arrhythmia before it can stop the heart. Since 1985, when the FDA approved the first implantable defibrillator, the number of device placements in the US has soared to over half a million.

There is no question that ICDs save lives. But because the device is implanted in the body – often remaining through a patient’s lifetime – it can also be life-altering. It requires testing and reprogramming (called interrogation) at intervals ranging from every one to every six months. Components of the ICD, including the battery, must be surgically replaced, generally between four and seven years after implantation. Moreover, as with any medical device, ICDs can malfunction (a 2006 study found that 2 percent of implanted ICDs were removed due to malfunction between 1990 and 2002) or become subject to manufacturer’s recall, which may require replacement of the device.

“While there’s a large body of research about both the clinical implications of ICDs and the ethics surrounding the decision of whether to implant one and when to deactivate it,” says Wojtecki, “few researchers have looked at how living with the device affects the people in the middle. It’s that middle period – between ‘We’ve saved your life’ and ‘Now do you want to end it?’ – that I want to talk about.”

Living with an ICD

Cindy Wojtecki Wojtecki’s doctoral dissertation, subtitled “‘Just Living’ or ‘Living for a Shock,’” paints a portrait of the tension patients experience between trusting in the device and striving for normalcy. She and advisor Meg Wallhagen found several surprising things when they analyzed data from in-depth interviews conducted with 24 ICD recipients. Among them was that participants assigned responsibility for the decision to obtain and maintain the ICD to medical experts.

Cindy Wojtecki Wojtecki’s doctoral dissertation, subtitled “‘Just Living’ or ‘Living for a Shock,’” paints a portrait of the tension patients experience between trusting in the device and striving for normalcy. She and advisor Meg Wallhagen found several surprising things when they analyzed data from in-depth interviews conducted with 24 ICD recipients. Among them was that participants assigned responsibility for the decision to obtain and maintain the ICD to medical experts.

“We talk about patient-centered care,” says Wojtecki, “yet the social norm admonishes: listen to the expert – your doctor.” She recounts the story of an elderly patient who was scheduled for an unrelated surgery and, at his doctor’s suggestion, had a concurrent second surgery to replace his ICD battery. The patient described a significant loss of stamina after the combined surgeries and dramatic deterioration in his quality of life. Wojtecki says, “He was very angry about it, and I wondered if he understood that it was his decision to make.”

Patients’ interpretations of the balance between the benefits and burdens of living with an ICD can change during the many years post-implant, says Wojtecki. And the study revealed a lack of opportunity, once the implant decision was made, for the patient and physician to have ongoing discussions about evolving options.

Wojtecki was also surprised at the apparent disconnect between patients’ stated desires regarding the end of life and their interpretations of ICD therapy. While none of the study participants – who ranged in age from 65 to 91 and had 2-19 years’ experience with ICDs – expressed an interest in deactivating their device, despite the discomforts and risks of replacing it, most also expressed a preference for a quick, “nonlingering” death.

“Everyone said they didn’t want life-sustaining treatment,” Wojtecki says, “but they didn’t view the ICD as life-sustaining.” Many patients, she says, first receive an ICD in their 50s or 60s, but as they get older, personal goals for treatments change. Yet there’s often no re-evaluation of the appropriateness of continuing ICD therapy. “Continuing is a social norm,” she says. “But as their health and illness status changes, do they still want to be assured that they’re not going to have a sudden death?”

Just Living Versus Living for a Shock

Living with an ICD can also have a significant effect on quality of life. One of Wojtecki’s key findings was that study participants described living on a continuum of well-being, with extremes at either end. Some, she said, reported “just living” with the ICD; life continued as it had before, and the ICD had little impact on most day-to-day activities and decisions.

At the other end were those whose lives were governed by an acute awareness of the device. These patients described living in a state of constant fear either that the device wouldn’t work when needed, or that they would receive a shock at an inopportune time – the state Wojtecki calls “living for a shock.” Most patients, she says, moved between these extremes over time, depending largely on ICD-related events, like a device recall or malfunctioning, as well as day-to-day events or plans for travel.

More Discussion Needed to Fully Inform Patients

The study raises important questions about decisionmaking and the impact of having a life-sustaining device implanted inside the body. It suggests that there’s a need for further discussion between patients, families and caregivers about what it means to live with an ICD, and for further research to develop intervention strategies that could foster conversations about device deactivation as an ongoing option for ICD recipients.

Says Wojtecki, “We think we know what we need to tell [patients], but after doing this research, I realized that I had no clue.”