Suzanne Bakken’s work includes research to improve the health of diverse populations in New York City.

Bringing Informatics to Health Disparities Research: A Talk with Alumna Suzanne Bakken

Suzanne Bakken is the Alumni Professor of the School of Nursing and Professor of Biomedical Informatics at Columbia University and co-directs the Center for Evidence-Based Practice in the Underserved and the Reducing Health Disparities Through Informatics pre- and postdoctoral training program at Columbia University School of Nursing. Her research focuses on promoting health and reducing health disparities in underserved populations through the application of informatics.

Dr. Bakken, who received her PhD from UCSF School of Nursing in 1989, received a UCSF 150th Anniversary Alumni Excellence Award, which was presented last May during the university’s Alumni Weekend in San Francisco. This May, she spoke with Science of Caring about her work.

SOC: How would you describe your work?

SB: My primary role is as a researcher at the intersection of informatics and underserved populations.

SOC: How did you find your way into that role?

SB: [In 1981], I was a critical care clinical nurse specialist and was hired by Cal State Stanislaus to teach a coronary care certification course. They had some grant funding and wanted to do some computer-assisted instruction, [and] I was primarily the content person.

One of the things I discovered was that I didn’t have the skills I needed to take it to the next level. So in 1984, I applied to do the doctorate at UCSF. Bill Holzemer [Professor Emeritus William Holzemer, now dean of the Rutgers School of Nursing] had been doing computer-assisted instruction for nurse practitioners, so that was the match. During the doctoral program I ended up studying the clinical decisionmaking of critical care nurses managing tachydysrhythmias [abnormally fast heart rhythms] using computer simulations. But I wanted to move from describing the decisionmaking processes to actually doing clinical decision support, so I went to Stanford to do my postdoc in medical informatics to focus more on decision support.

SOC: What was the state of biomedical informatics at the time?

SB: People would say the earliest work in artificial intelligence, which was around diagnosis and management of medical things, started in the late ’70s to the early ’80s. Stanford was a big hub for that. There was some work in electronic health records going on, but nursing was about computer applications for nursing. By that I mean, people were saying, “This is how you could use a computer to support nursing practice; this is how nurse administrators could use a computer. This is how a nurse researcher could use a computer.” At that point, nurses were not formally prepared in the field of medical informatics and biomedical informatics.… Judith Graves, at the University of Minnesota, was the first nurse to ever have a postdoc in medical informatics in one of the National Library of Medicine training programs. I was the second overall, and the first at Stanford. Things have obviously changed dramatically in terms of the training opportunities, with more nurses getting PhDs and doing postdoctoral training in biomedical informatics.

SOC: How has your work in clinical decisionmaking support evolved?

SB: Over the years, I’ve thought a lot about how to use different types of information technology in the context of improving care. In particular, I led a large randomized, controlled trial, funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), [in which] we created mobile applications that would support guideline-based care for four [health concerns] in adults and children: obesity, overweight, smoking and depression. Our trial showed that with the use of our mobile decision support system, nurse practitioners-in-training were more able to diagnose each of those conditions, there were higher screening rates, and in two of the four conditions [obesity and depression], there was more guideline-based care delivered. The final report of the full randomized, controlled trial [“The Effect of a Mobile Health Decision Support System on Diagnosis and Management of Obesity, Tobacco Use, and Depression in Adults and Children”] just came out [in 2014] in the The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. There was quite a bit of press about it.

SOC: At one point, you began focusing on health disparities. Can you give us some examples?

SB: My most recent work has focused on the Latinos that live in the Washington Heights-Inwood neighborhood[s] of New York City, where Columbia University Medical Center is located. I recently led a $9 million Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality-funded project. The basic idea was to be able to do comparative effectiveness research related to these populations. It was important to pull together multiple data sources, so we had our clinical data warehouse from NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, plus data from other clinical agencies and outpatient clinics. You can think about the clinical data representing how people look when they’re sick. Then we added this large survey [of around 6,000 Latinos in the area] to get social determinants of health and health behaviors, and were able to join those things together for the study. We also collected biospecimens for genomic studies on about a third of the survey participants, so we now have a great foundation for precision medicine, because we have phenotypic data that would come from the survey and from the electronic health record combined with the genomic data that can come from the biospecimen. Thinking about precision medicine as genomic data alone is limited. The recent Varmus and Collins article [“A New Initiative on Precision Medicine”] in The New England Journal of Medicine makes it very clear that precision medicine is beyond the genes.

That can facilitate all kinds of research studies in many people, and we make it available as a resource to others, because that was the intent of our funding. The part of it I’m most excited about now, though, is the community engagement part. There are historical issues of getting individuals who’ve been traditionally underserved and are at high risk for health disparities to be involved in research. It’s really important that we work with them to gain their trust, thinking not only about times when they’re patients, but when people are simply themselves living in their community in their nonsick roles.

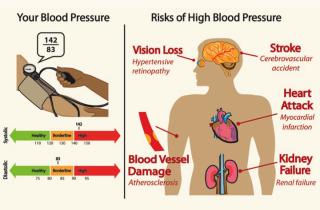

We also created infographics, which are information visualizations that we specifically designed for individuals with low health literacy. We did participatory design with the community members to come up with the designs. Now we’re in the process of feeding information about health behaviors and other patient-reported outcomes back to the community members, so that they can engage in self-management.

Example of infographic Historically, there’s been a lot of talk about “make it simple,” but the most important thing we learned in working with our community is that it’s actually not true for them. These people, who were primarily Hispanic with inadequate levels of health literacy – if you gave them pieces of information without context, they didn’t get it. So it was actually the more complex infographics that were the most understandable and perceived to be the most useful and actionable to them. For example, our participants preferred a blood pressure infographic that included not only numbers and interpretation but also displayed potential risks associated with hypertension (see example at right).

Example of infographic Historically, there’s been a lot of talk about “make it simple,” but the most important thing we learned in working with our community is that it’s actually not true for them. These people, who were primarily Hispanic with inadequate levels of health literacy – if you gave them pieces of information without context, they didn’t get it. So it was actually the more complex infographics that were the most understandable and perceived to be the most useful and actionable to them. For example, our participants preferred a blood pressure infographic that included not only numbers and interpretation but also displayed potential risks associated with hypertension (see example at right).

We [also] make all of our designs freely available to other people to test.

SOC: What opportunities do you see for informatics changing the landscape for health disparities?

SB: One thing is that, historically, there are differences in the way clinicians screen and manage particular racial and ethnic minorities compared to people who are white. So implementing clinical decision support systems, such as the program I talked about earlier that was focused on depression, smoking cessation, and overweight and obesity, we’re able to show that we can make those screening disparities go away.… You’re not less likely to be screened if you’re part of a racial or ethnic minority. So putting those things in place helps guideline-based care to be more equitable.

Then we can bring more information directly to the patient or the person in the community; we can work with them to make sure, as I described, that anything that we do is user-centered to meet their needs, that it’s at an appropriate level of health literacy, is culturally relevant, and we can use informatics strategies to deliver tailored information to individuals. We know that if we can make it more tailored to their perspective, people are more likely to engage with the information and to take action based upon it.

Mobile health has amazing potential for reducing health disparities as well, because although racial and ethnic minorities in particular have been less likely to have home computers, they’re actually more likely to have mobile devices, including smartphones. It facilitates us being able to deliver content at the point of need. Our group at Columbia spends a lot of time thinking about mobile apps and other ways of reaching people who typically have been considered at risk for health disparities, such as people with HIV/AIDS, the elderly, low-English-proficient, low-literacy individuals, including the Latinos that I work with.

SOC: What are some of the challenges?

SB: I’ve been writing a couple of thought pieces on big data that have just been accepted for publication. In one of them, I’m thinking about what they call the ELSI issues – the ethical, legal and social implications – specifically for people at risk for health disparities. Although it’s really exciting to think about this increased data availability, we need to consider a couple of potential perils, one of which is that you can end up with biased data sources. If you end up with a data source that has very few racial and ethnic minorities in it, you then lack the potential to make discoveries that could influence their health or treatments for them.

The other thing I worry about is that individuals may be unknowingly contributing data to data sources that someone else takes and commodifies and makes money from. It’s OK if you know you’re doing it, but I worry that if you have low English proficiency or speak another language, or just are tuning into this, that you’re unwittingly donating data…about your health behaviors, your food and exercise patterns, the places you go – there’s so much info that can be gained. Places like PatientsLikeMe do commodify the data, particularly for Pharma, but people are well aware going into it, and people are also aware of the benefits they gain by participating, which include a social support network and different types of data that are informative for them. It’s not one-way. But you want that value proposition to be there and have people be aware.

Technology and sociocultural and political context of technology use evolve rapidly, so I’m never bored with my research area. The outstanding PhD education that I received at UCSF equipped me well to change with the times.