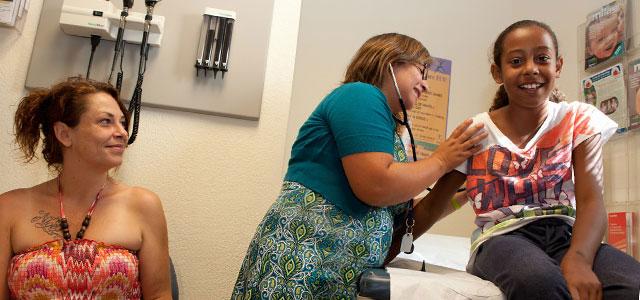

Jesahel Alarcon at Napa’s Community Health Clinic Ole (photos by Elisabeth Fall)

PrimeRISK: Learning to Care for the Most Vulnerable Among Us

At a bustling community health clinic in the vineyard-dotted Napa Valley, a middle-aged woman with diabetes confesses to her clinician that she lost her job at a hotel and can’t afford insulin. It’s been six months. She’s worried. She doesn’t feel well.

At a San Francisco clinic specializing in sexually transmitted diseases, patients have pressing questions about a new drug shown to prevent HIV infection.

At a community clinic in downtown San Francisco, a man in his 50s groans about chronic pain so bad he can’t walk. And he has other problems: hypertension and hepatitis C.

Though it’s unlikely they know it, all of these patients have something in common: They’re getting care from family nurse practitioners (FNPs) who received specialized training in serving vulnerable populations and who sought jobs in communities that at least to some degree remind them of themselves.

Family Practice in High-Risk Populations

“One thing I really appreciate is when I have African American patients tell me it’s really nice being helped by someone who looks like them,” says FNP Erica Bagby, who works at San Francisco’s South of Market Health Center, where she is treating the gentleman with debilitating pain. “They’re more comfortable; they’re more open. It makes me feel blessed.”

Bagby – along with Jesahel Alarcon, a practitioner at Napa’s Community Health Clinic Ole, and Tony Sayegh, a clinician at the San Francisco City Clinic – is a graduate of the UCSF School of Nursing’s Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP) master of science program, which prepares primary care clinicians for community-based settings.

As part of the program, they’ve all taken courses in a UCSF School of Nursing effort called PrimeRISK (Primary Care of High-Risk Populations). This special program, now a decade old, exists thanks to grants from the Health Resources and Services Administration, the federal agency charged with improving access to health care for the uninsured, isolated and medically vulnerable.

The grants help enhance curriculum in areas of striking need. This includes developing coursework and clinical sites focused on treating homeless, substance abusing incarcerated, chronically mentally ill, high-risk elderly, and immigrant populations. The program has funded an overview course in public health epidemiology, a class on caring for underserved and vulnerable elderly populations and a class in the clinical management of conditions associated with these populations.

“We prepare students to treat underserved populations and patients with a myriad of health care needs, across the life span,” says Ellen Scarr, who coordinates the UCSF FNP program.

As part of their FNP training, students master basic primary care, from diagnosing and treating chronic conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure and asthma, to performing minor office procedures and prescribing medicines.

But thanks in part to PrimeRISK, their focus extends far outside the examining room.

“We look at the whole picture; the patient’s environment, family situation, emotional state – all of these impact health,” Scarr says. “We also look at how well our curriculum is meeting the needs of our graduates. Their workload has become a lot more complicated; they’re seeing more patients, they’re managing cases that are more complex. There’s a whole overlay of psychosocial needs that complicate care.”

Whole-Person Care

It’s precisely the complexity of cases and the “whole person” approach to primary care that attract many to UCSF’s FNP specialty, graduates say.

“I was looking for a long-term human connection,” says Alarcon, a 2011 graduate who now has a busy practice at Napa’s Clinic Ole, which serves a large number of low-income, uninsured Spanish-speaking immigrants.

Alarcon, whose mother was an oral surgeon in Mexico City, had been accepted to UCSF’s School of Dentistry but longed for a health care career that would reach family health needs more broadly.

“We’re one of the few true family practices in Napa seeing everyone cradle to grave,” she says. “It’s definitely my population of interest. It goes back to seeing poverty in Mexico as a child – knowing that we depend on these people as workers is moving.”

As a gay male who grew up in the Bay Area, Sayegh understands the emotional struggles that can be part of being a sexual minority – and the unhealthy behaviors to which those struggles can lead, including drug and alcohol abuse and risky sexual behaviors.

Driven to help young gay men avoid unhealthy traps, Sayegh graduated from the FNP program this year. He was recently hired at the SF City Clinic, the municipal sexually transmitted disease control and prevention clinic, working with patients enrolled in a pilot study on the feasibility of using daily antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for preventing HIV infection. He'll also provide clinical care.

“Family nursing not only incorporates medical care, but it takes into account psychosocial concerns that affect medical health. There’s a huge interplay between the two, and it really provides an artful approach to providing care,” says Sayegh.

Diverse Providers for a Diverse Country

One of PrimeRISK’s biggest successes is its ability to attract a diverse student body – a primary goal at both the School of Nursing and UCSF in general. Achieving the goal can be challenging, however, especially with tuition increases and budget cuts to college loan and grant programs.

Even so, with help from PrimeRISK, the FNP program is doing a decent job, Scarr says, adding that it can always do better.

- Sixty-two percent of 2011 graduates are from ethnically diverse backgrounds (data from the last three years show that the diverse graduates are mostly Latino but also Asian and African American).

- Fifty-six of the 62 enrolled students in 2012 speak a second language – mostly Spanish, which is almost essential for placement in community clinic settings in the Bay Area.

Of course, representing the ethnic background of your patients isn’t necessary for providing excellent care, but it can make a tangible difference, especially in the flow of honest, open communication, Scarr and other practitioners say.

Plus, she says, “From an academic perspective, having a diverse student population makes for an incredibly rich learning environment. We learn from each other.”

For FNP Grisell Ramirez, being a native Spanish speaker allows for a trust that helps Latino patients more freely discuss personal issues that impact health, such as abuse or loneliness. “I can say, for example, ‘Well, tell me about your family; I know there’s more to you than just you.’”

A 2012 graduate, Ramirez, a California Central Valley native, is working as an RN at a Fresno hospital while she job-hunts in community care. She’s optimistic and excited.

“I worked with a lot of Spanish-speaking people, especially women, and saw a lack of health education and a gap of care for them,” she says. “I wanted to be an FNP because I want to be able to influence my people before they get to intensive care or the hospital.”

Expanding Job Field

With growing national shortages in primary care doctors, FNPs are positioned well for employment, Scarr says. Those with PrimeRISK training are especially well positioned, because shortages are most pronounced in underserved communities.

Data support the program’s goal of reaching the neediest populations. Surveys of graduates from the past few years show the following:

- Spring 2011 (18): 67 percent working in primary care, 83 percent with the underserved

- Fall 2010 (4): 50 percent working in primary care, 75 percent with the underserved

- Spring 2010 (27): 78 percent working in primary care, 74 percent with the underserved

- Fall 2009 (4): 75 percent working in primary care, 75 percent with the underserved

Scarr notes that these results are especially impressive because community-based care often pays less than hospital-based care, so community-based FNPs must be highly motivated nurses. Many students, including Bagby and Ramirez, come to the program as working RNs knowing they’re training for settings that may pay less. “It can really be a pay cut for them,” Scarr says.

But for many of the program’s participants, motivation is the easy part.

“I have a huge interest in catching high-risk youth before they fall,” Sayegh says.

Raya Duenas, a recent grad who is working at a community clinic in New Mexico, earned a master’s degree in public health and worked in policy for a few years before heading back for her FNP certification.

“I did some soul-searching,” she explains. “I felt too far away from the people sitting [in front of my] computer.”

Besides, getting closer to patients pays its own dividends.

The Napa woman with diabetes is back on insulin and hooked up with a program that helps pay for it.

The high-risk patients at SF City Clinic may now have a new strategy to protect them from HIV infection.

And the San Francisco gentleman in chronic pain is doing much better.

“We [formulated] a plan together: physical therapy, exercise, stretching,” Bagby says. “He went from a wheelchair to a walker to a cane.”