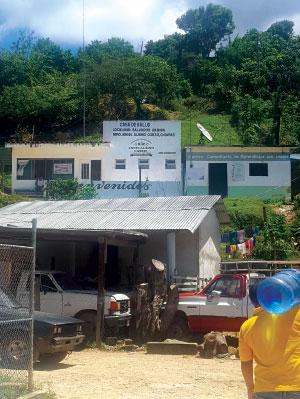

Carolina Noya (kneeling, third from left) joins patients, providers and community health workers at the first shared medical appointment in a rural community clinic in Chiapas, Soledad.

Clinical Innovation Changes Lives for People with Diabetes

The human costs of diabetes – which as of 2017 affects approximately 425 million people around the world – are devastating. The disease is a major cause of blindness, kidney failure, heart attacks, stroke and lower limb amputation, as well as depression and stress, which afflict many people struggling with chronic illness. The mental health challenges are often tied to the fact that effective diabetes management is a relentless task – a daily, at times hourly struggle that involves monitoring blood sugar levels and managing diet, exercise and medications. Ideally, it also involves a close partnership with one’s provider.

Yet even in communities with strong access to care, it’s nearly impossible to jam everything that needs to be done – physical exam, medical management and patient education – into the typical 20-minute appointment. In communities where challenges ranging from inadequate insurance through language and cultural barriers compromise access to quality care, even less-than-adequate appointments are few and far between.

In 2015, these facts inspired nurse practitioner (NP) Carolina Espinosa Noya to modify the shared medical appointment (SMA) concept to help her medically underserved patients with type 2 diabetes at Santa Cruz’s East Cliff Family Health Center. At the time, Noya was also a PhD degree student at the UC San Francisco School of Nursing, and her version of the SMA eventually became the centerpiece of her doctoral dissertation. The model, named ALDEA (Latinos con Diabetes en Acción), the Spanish word for village, has now spread to multiple clinics in California’s Central Valley and to Chiapas, Mexico, with Noya, today a member of the School’s faculty, playing an important role in the implementations.

The Modified SMA

SMAs have been around for decades, ever since the Veterans Health Administration and health maintenance organizations recognized that group appointments are an opportunity to more efficiently deliver quality care to more patients. In contrast with a 20-minute individual visit, the SMA is typically a two-hour appointment staffed by a multidisciplinary team serving a group of eight to 12 patients. Each patient receives his or her physical check, but also gets considerably more time for education and support, including peer support.

Noya saw the potential for her patients with diabetes, and wanted to use her experience working in community clinics with underserved patients to adapt the model. She also envisioned NPs leading the sessions – a departure from traditional SMAs, which typically exclude advanced practice nurses. With the help of a Health Resources and Services Administration grant, she crafted a version in which a group of her patients with type 2 diabetes defined each appointment according to their particular needs. This enabled the team to more directly address patients’ concerns about any aspect of managing their disease.

“The patients’ ownership of the process is key, because it creates belonging, which translates into patient activation and behavior change,” says Noya. “In most other types of patient education, people get a few minutes with a nurse or go to a class and then they’re done, but here they have more control and also get more time and ongoing support, all of which are important.”

For example, in one session, the group chose to make licuados, a type of Latin American smoothie, as a way to learn about the role of fruits and carbohydrate counting in managing diabetes. The approach was more impactful than reading a handout, especially for low-literacy patients.

Noya says that the model also changes the clinician’s role in patient education. “I am a facilitator, filling in gaps and correcting misinformation, but the patients are the experts, and they teach each other as they create a community of people living with diabetes, who walk together.”

Noya’s study of her initial implementation found that her model increases access to care for this patient population and significantly improved hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels, which matters because the literature indicates that even a one-percentage-point reduction in HbA1c levels can positively change the course of the disease. Noya also found that patients identified substantial positive impact from having the opportunity to share their experience with other individuals living with diabetes – an impact that appears to go beyond managing the disease into many other aspects of these people’s lives.

Spreading the Word to California’s Central Valley

A HRSA grant provided Noya the opportunity to bring this model to rural Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) in the Central Valley of California. Beginning in 2016, Noya became a consultant and trainer as Community Medical Centers in Stockton, Altura Centers for Health in Tulare and Camarena Health in Madera began creating their own versions of the SMA. Noya encouraged the modifications in the belief that each place must make the model work in its unique setting.

Initial meetings included a wide range of stakeholders at each FQHC, from the chief medical officer through billing clerks. Each chosen team visited Noya’s SMA program in Santa Cruz – and Noya, in turn, observed each team once implementation occurred, to provide feedback and guidance. The SMA teams from participating clinics met with Noya monthly in order to support each clinic through the process.

“Part of my role was to train people in facilitation, which is a very different skill set for many of us,” she says. “The model seems to consistently generate positive results, but a good facilitator brings it to another level.”

After an English-speaking pilot, Community Medical Centers began with two groups, one for English speakers and one for Spanish speakers. Nurse practitioner Elizabeth Castillo, who now runs the School’s Rural Health Minor, leads both groups, along with a health educator, a medical assistant and a medical receptionist. They targeted patients with HbA1c levels above 9 percent (the American Diabetes Association recommends that patients with diabetes keep their HbA1c levels below 7 percent).

“The patients have become very committed,” says Castillo. “People want to see the HbA1c reduction, but it has to be more than a one-time reading; keeping HbA1c down is more important, and that’s where these groups really help. I can’t recall any of these patients being hospitalized for complications or ever having an ER visit since we began.”

Altura began with a Spanish-speaking group – also targeting patients with HbA1c levels above 9 percent – which internal medicine physician Raquel Ramos runs, in part because, at the time, the clinic had no Spanish-speaking NPs. The team also includes a health educator and a medical assistant. “We plan to see a maximum of 15 people per session, and we added an extra hour to complete documentation,” says Ramos.

The group was so successful, with such steady participation, that Altura opened an English-speaking group, but it did not draw the same interest or commitment. Thankfully, those who did come are bilingual and have shifted to the Spanish-speaking group.

Ramos says that some of the patients support each other outside of group appointments by taking walks or going to Zumba classes. In addition, she says, “The patients have all learned a lot about how to eat better and make lifestyle changes. One woman is now talking about food groups and carbohydrates – it’s really amazing the way the language she uses has changed.”

All three clinics have been able to roughly replicate the results that Noya produced in her original study. Both Altura and Community Medical Centers are expanding the SMAs to other clinics in their networks.

From the Central Valley to Mexico

Rural clinic in Chiapas, Mexico Around the same time as the work began in the Central Valley, rural clinics in Chiapas, Mexico, caught wind of Noya’s work through UCSF’s HEAL Initiative. In 2016, while he was in San Francisco for a meeting of the initiative, Compañeros En Salud Executive Director Hugo Flores Navarro (Compañeros is Mexico’s arm of Partners In Health) was urged to pay a visit to Noya in Santa Cruz. Nearly immediately, he decided SMAs were a must-do for Chiapas.

Rural clinic in Chiapas, Mexico Around the same time as the work began in the Central Valley, rural clinics in Chiapas, Mexico, caught wind of Noya’s work through UCSF’s HEAL Initiative. In 2016, while he was in San Francisco for a meeting of the initiative, Compañeros En Salud Executive Director Hugo Flores Navarro (Compañeros is Mexico’s arm of Partners In Health) was urged to pay a visit to Noya in Santa Cruz. Nearly immediately, he decided SMAs were a must-do for Chiapas.

Despite Mexico’s promise of universal health care coverage, rural regions like Chiapas – a huge geographic area with a population of only 5.2 million people – often are not able to offer full access. That was what brought Partners In Health to Mexico to create a mixed model of delivering care in Chiapas, in collaboration with Mexico’s Ministry of Health.

In one aspect of its work, Compañeros recruits recent graduates of Mexican medical schools, who are required by law to fulfill one year of social service. Called pasantes, these physicians receive supervision, mentorship and training; many choose to remain past their required year to help supervise the next generations of recruits. Sebastián Mohar Menéndez-Aponte fits that description.

A pasante when Noya made her first visit to Chiapas in 2017, Mohar stayed on as a clinical supervisor, and when Noya returned in 2018 to help jump-start an SMA pilot, he volunteered to oversee the effort, along with his colleague Martha Arrieta Canales. The trio agreed that Chiapas faced particularly steep challenges in addressing diabetes, including limited food choices, malnutrition and insulin shortages. Getting people to the clinic regularly for SMAs might pose an additional challenge, given the distances some have to travel.

Together they made some modifications to the model and launched a small pilot in four different community clinics, with two master’s degree students from the School participating in the early days. In addition to a physician supervisor, the clinical teams include a community health worker, a nurse and a pasante.

“Caro [Noya] brings all this know-how and experience, but she always allows for local knowledge to take control,” says Mohar. “She is very open to learning from our experience.”

An initial evaluation of the pilot provided evidence that both patients and providers liked the model, with the majority of patients preferring the SMA visits to individual visits – and convinced the team to move ahead. In its successful grant proposal to a private funder, the Compañeros team included an expansion of SMAs – aiming to triple the number of patients, from 40 to 120, by March 2019 and expand to one additional clinic – as well as funding for Noya to study the implementation in a randomized controlled trial.

While the pilot groups continued functioning at full strength, a number of factors pushed back the starting time and expected numbers for the expansion. Nevertheless, by December 2018, the Chiapas team had established its new groups in five clinics and has now enrolled 100 patients. As in Santa Cruz and the Central Valley clinics, the Chiapas program appears to be having a very real impact, including reductions in HbA1c levels, strong attendance and additional benefits.

“The patients are very happy, and despite going against what we’ve been taught, the doctors are adjusting well to not being center stage during the consultations,” says Mohar. But he says he’s most impressed by the way SMAs normalize diabetes for the patients. “It is a disease you’ll carry for the rest of your life, but you don’t have to do it alone anymore. When people who have had great control for six months fall, other patients cheer them on and get them back on track. We are in this together, and that takes away pressure from both the patient and provider.”

The Power of Connection

It is that sense of community that seems especially powerful for patients and providers alike, offering a real opportunity to scale the model for diabetes and adapt it for patients with many other chronic diseases.

“Health care has changed so much, and the group offers me an opportunity to get to know patients as people and establish relationships that help improve compliance,” says Ramos. “I enjoy it very much.”

Castillo agrees. “The patient-to-patient connection is just so beautiful to witness,” she says. “And seeing the patient more frequently, you make a different connection than you would in a confined space for 15 minutes. It’s so helpful for me as a provider, but also for the patients, who are actually happy to be here. That happiness is incredibly contagious.”

It also has enormous potential for changing people’s lives. Noya tells the story of an immigrant patient whose poverty and isolation from his family had driven him to suicidal thoughts. After experiencing the sense of community in the group sessions and learning about mental health resources – SMAs can be a bridge to mental health services among populations that often lack access or feel hesitant to pursue this resource – Noya says, “He took a 180-degree turn. It’s a powerful thing to see when that happens.”